Yesterday was a very sad day for me – not just because Stephen Downes’ cat has died, you have my sympathies, Stephen – but also because the United Kingdom has finally and completely exited the European Union.

Since I emigrated from Britain 30 years ago, I have carefully avoided getting involved in British politics. However, when even members of the Royal Family start emigrating, you know that something terrible has gone wrong. (Incidentally, rumour has it that Harry and Meghan will be living just down the road from me. He will be most welcome so long as he gets a job. We are desperate for waiters here in Vancouver, and during the day he could go to college and take a plumbing apprenticeship – can’t get a plumber in Vancouver for love nor money.)

More seriously, what a sad day. When I was living in England I worked on several distance education and technology contracts from the European Union. This brought me into contact with educational technologists and distance educators from all over Europe. Most projects required a team drawn from across several countries, including those working in the less developed countries in the EU at that time. I really enjoyed working on these projects. It is not always fully understood in North America just how diverse the cultures are across the different European countries. In two or three hours you can drive through at least three completely different cultures: different food, different dress, different manners, different languages. The result of removing hard borders was that people who previously hated each other not only learned to get along, but began to like each other.

I worked on a very interesting satellite project where medical education was being broadcast into southern and eastern Europe via the OLYMPUS satellite. In 1991 (after I had left for Canada), control of OLYMPUS was accidentally lost, following an uncontrolled orbital drift around the world, in a frozen state at temperatures of some minus 60 degree Celsius. Nevertheless the satellite was the subject of a spectacular recovery action which allowed it to be put back into service again – except by then it had used up all its fuel. The rumour (once again) has it that when control was lost an Italian technician was trying to tweak the satellite so that it could broadcast an Italian soccer match. Nevertheless, the project was a typical European Commission project: ambitious, hilariously managed, great fun, and at the end of the day, some useful lessons were learned (but not the ones intended).

However, the seeds of the problems of the European Union were already there before its rapid expansion following the collapse of Communist Europe in 1989. Before then there were 12 member countries. Even then, the European Commission (EC) was heavily bureaucratic. For instance, every project I worked on had to have researchers from at least five different countries, one of which at least had to be from Southern Europe, and include at least one European commercial company. Ensuring all countries were equally represented in the hiring of EC staff meant that often EC project managers had no expertise in the area they were managing. The goals of economic integration, equal representation and ‘balancing’ the economies in Europe took precedent over effective research projects. Nevertheless, to some degree the strategy worked well. Less advanced countries were brought up to speed with what more advanced countries were doing. Money flowed from the richer countries to the poorer countries. And things did get done, if more slowly than was ideal.

However, 2004 was a critical turning point. The EU almost doubled its membership overnight with the addition of 10 more countries, and two more in 2007, nearly all from the former communist Eastern Europe. Again, the goal was impeccable: ensure the former communist countries were fully integrated into the European Union. But it was too much, too fast. There was too great a difference between the rich and poorer members of the union. Immigration from poorer to richer countries soared, creating tension. The common currency of the euro was stretched to its limits by the difference in purchasing power in different countries due to the differences in the strength of their economies. And above all, the bureaucracy of the European Commission became even greater, slower and more out of touch with reality. Finally, getting 28 such diverse states to unanimously agree on everything is somewhat challenging, to say the least.

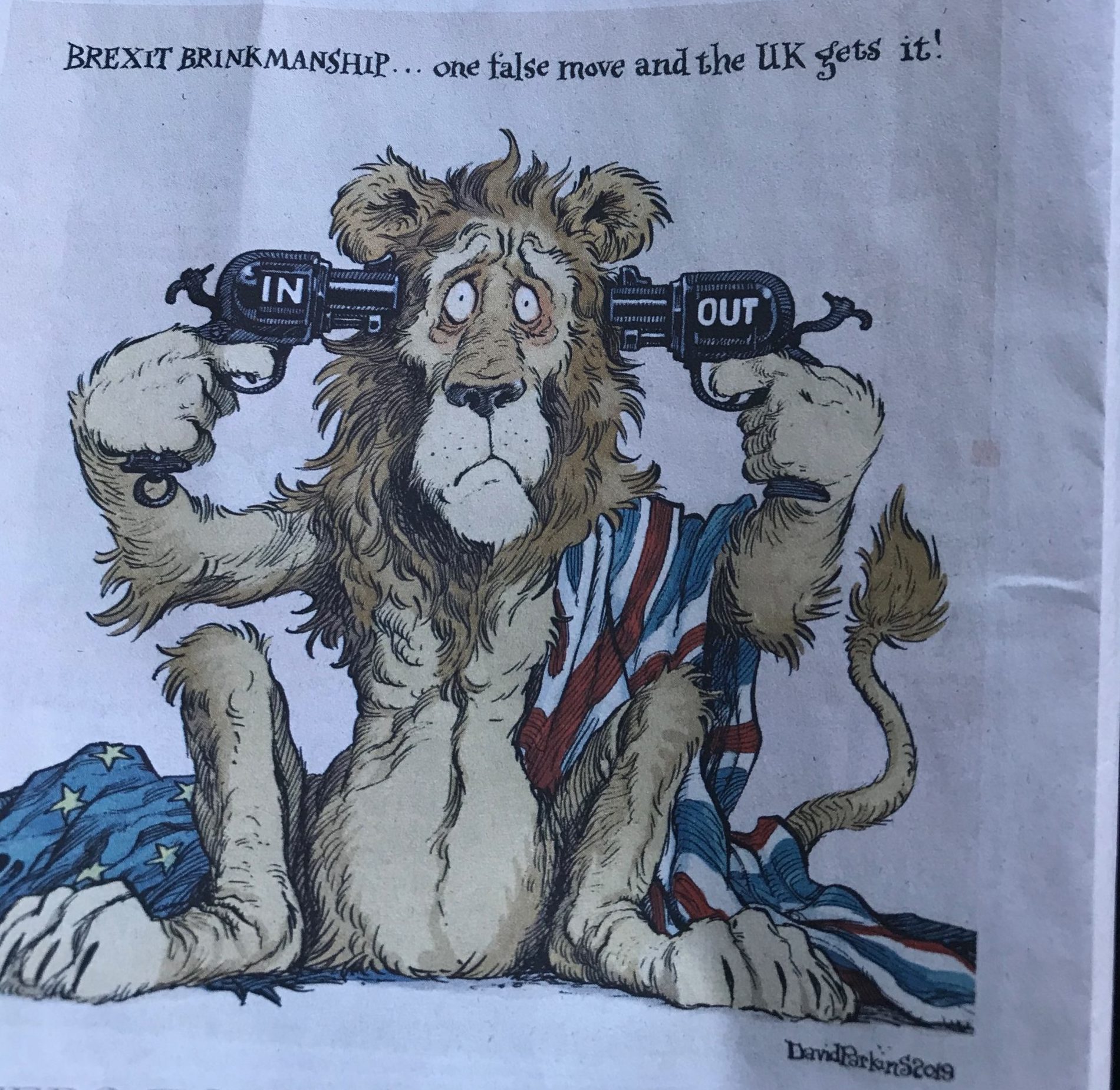

So I was saddened but not surprised when the Brits voted for Brexit. This was the result of a cynically mendacious campaign by the Brexiteers, who blamed all Britain’s serious problems, such as long-term unemployment in former industrial areas and starved and privatised public services, on the European Union and immigration, cleverly deflecting criticism away from the Conservative Party who had governed Britain for the past 20 years – and are still in power as a result. (And don’t get me started on Jeremy Corbyn, who went missing in action, partly because he doesn’t believe in free trade, which he sees as a capitalist conspiracy).

Europe loses, because, for all its faults, Britain was one of its more economically advanced countries, the central financial centre for Europe, and a strong contributor to the culture and richness of Europe. Europe needs a strong, still mainly democratic country such as the UK in a world teetering towards fragmentation and right-wing extremism. Most important, after many wars fought between European countries, the EU was founded to bring peace and harmony to Europe. Britain leaving the EU is a betrayal of that ideal. Europe is now even more politically vulnerable to splintering and right-wing extremists. A future war between European countries edges closer, and a weakened Europe is now more vulnerable to Russian mischief.

Sadly, though, the biggest loser here is my old country. Only the hubris of the British can enable them to ignore not only the economic consequences but the long-term political risk of leaving the EU, risk both to the UK and to Europe. First, the risk to the UK. It is now strongly possible that Scotland will leave the United Kingdom, and possibly even Northern Ireland will find itself stronger as part of a united Ireland still in the European Union, although I doubt whether economic sense will prevail over religious dogma in the north. And good luck, England, negotiating a trade deal with Trump’s America. Don’t expect the EU to be generous, either, in any re-negotiated trade deal. Britain would have been far better off committing to Europe but working to change its governance to make it more streamlined and efficient.

However, Britain’s major problems (chronic unemployment, poor public services, increasing income divides) have not gone away. They still need to be fixed – and the EU can no longer be blamed. Maybe one day Brits will wake up to the fact that they have been stitched up by a ruling elite who run things for their own benefit.

But the saddest part of all is what is happening to the young in Britain, who voted overwhelmingly to stay in Europe. It doesn’t stop with Harry and Meghan. The brightest and the most able young people are moving out. I’m listening to my sons and my grandchildren who are still British citizens. A niece is looking to move to Sweden; one grandson is applying to American elite universities; one son is looking for ways to come to Canada (I’ve suggested Halifax. Love my family, especially at a distance). They want out and have the education and wherewithall to leave. Many don’t, though. The young see no future in Britain. And that hurts.

So, yes, it’s good that at last the uncertainty is over. But death is also certain. Which is why I am sad today.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Absolutely wise and true words, thank you Tony! With the irony (English, isn’t it…?) even enjoyable 🙂

I have worked in many EU educational projects since about 1991 and they have enabled me to develop my expertise in leaps and bounds. I have to say that I think that the inefficiency of the EU bureaucracy is a myth or at least, has decreased markedly over the years. The EU is seeking to be efficient as well as effective and is streamlining and simplifying procedures (it is no longer necessary to ensure the geographical spread in projects anymore for example). And all that with a staff equivalent to that of a large city administration. Birmingham is the example often used. Yes of course the EU is not perfect but it is moving in the right direction and taking up many worthy causes that other blocks neglect, such as climate change. I think the EU was never really present in the school curriculum in the UK plus the media have wrought their worst over decades and been allowed to get away with it all that time. It is diificult to dismiss the drip, drip, drip of misinformation over decades. I too am sad at what I have witnessed in my country since 2016, but am happily and securely settled in Denmark.

Thanks for your comment, Anne. Glad the bureaucracy has got less over the 30 years since I was last involved! And Denmark is one of my favourite European countries.