Zawacki-Richter, O. and Jung, I. (2023) Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Learning Singapore: Springer

Review of ‘Organization, leadership and change’: Part 2

You may remember I have already reviewed 33 chapters, including the first six chapters of Part IV. This post will review the remaining six chapters in Part IV, on organization, leadership and change. The review of the first six chapters of Part IV can be read here. The last six chapters of Part IV are:

- 34 ODDE and Debts, by Thomas Hülsmann

- 35 Institutional Partnerships and Collaborations in Online Learning, by David Porter and Kirk Perris

- 36 Marketing Online and Distance Learning, by Maxim Jean-Louis

- 37 Managing Innovation in Teaching in ODDE, by Tony Bates

- 38 Transforming Conventional Education through ODDE, by Mark Nichols

- 39 Academic Professional Development to Support Mixed Modalities, by Belinda Tynan, Carina Bossu, and Shona Leitch.

This post is followed by another tomorrow that provides a reflection on all 12 chapters in this section.

Declaration of Interest

Not only do I have my own chapter in this section, but many of the other chapters are written by colleagues and close friends. I have a particular interest in these chapters which will of course influence my review.

Chapter by chapter review

34. ODDE and Debts: Taking Account of Macroeconomics, pp.564-584

This chapter, by Thomas Hülsmann, of the University of Oldenburg, Germany, argues that DE has focused on driving down costs and devolving costs to the students, ….cost efficiency gains have often not been handed to the learner, leading to rises in tuition fees and, consequently, student debt.

The second half of the chapter introduces modern money theory (MMT), a different economic paradigm, which suggests that monetary sovereign countries have enough policy space not to focus narrowly on driving down costs. It notably suggests that devolving costs to students turns out, from the MMT perspective, to be misguided.

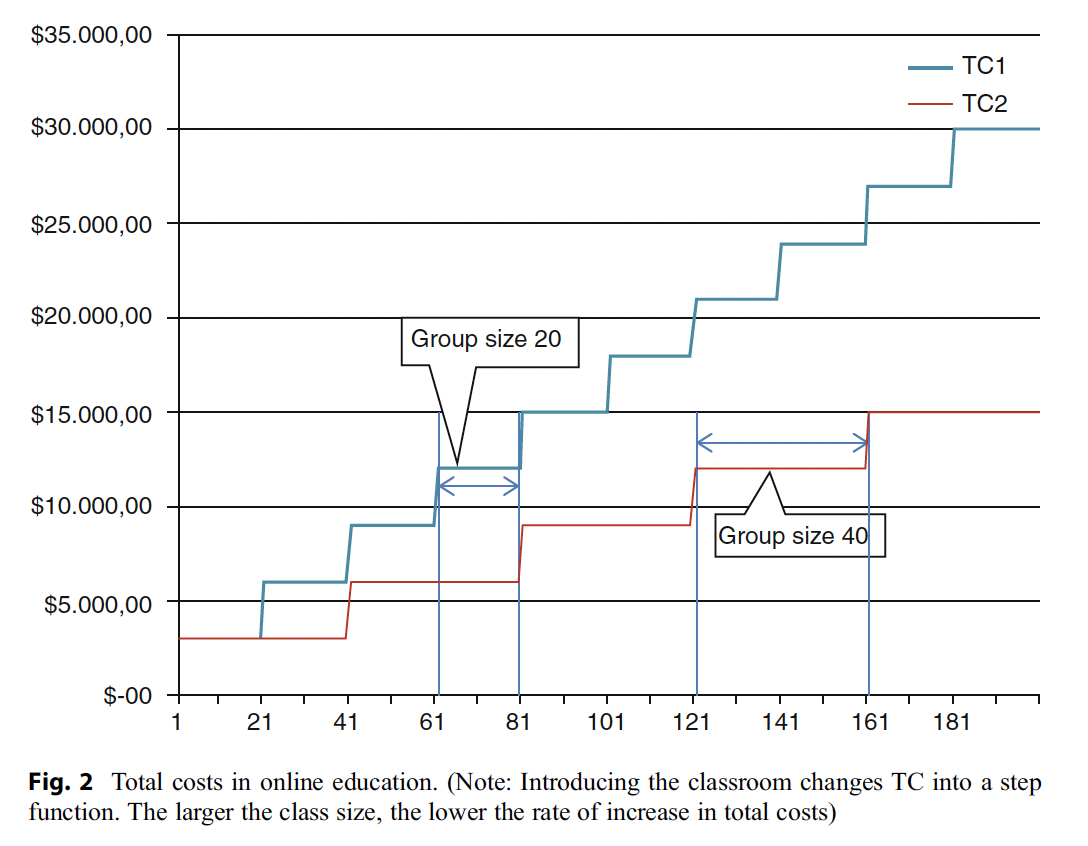

The first part of this chapter is a useful re-iteration of the microeconomics of distance education. Basically the claim is that DE will always be cheaper than campus-based education, because of economies of scale, automation of (some) learning activities, lower fixed costs (e.g. buildings), and lower labour costs. However, most institutions do not pass these savings on to students: tuition fees are the same or even sometimes higher for DE courses.

More importantly, although the cost-efficiency of DE over campus-based teaching may be true in theory, in practice this is not always true, partly because capital overhead costs (buildings, heating, etc.) of in-person teaching are excluded or ignored by administrators. The catch here is instructor:student ratios. Many large lecture courses are more cost-efficient than smaller, online classes. The difficult part to measure is the outcomes: do students learn more or better at the same cost or less? Another problem is that educational institutions do not use activity-based costing for decision-making (which would mean actually costing out each course or program by mode of delivery). Cost-effectiveness will always depend on other factors other than the mode of delivery, such as the quality of the instruction or the instructor:student ratios.

Hülsmann’s explanation of modern monetary theory (MMT) is interesting. Under MMT, there should be no student debt, as debt repayment takes away money that could be used productively in the economy. (This is an argument against all student debt, not just distance learners’.)

I really enjoyed reading this chapter, despite Hülsmann’s tendency to use mathematical formulae and acronyms to describe relatively simple relationships. The chapter would have benefited from some actual cases of cost comparisons between similar courses or programs delivered online versus face-to-face. Economics may be fine in theory, but reality tends to be too messy for a strict cost-benefit analysis. But this book needs a good chapter on costs, and Hülsmann provides it.

35. International partnerships and collaboration in online learning, pp. 585-604

This chapter, by David Porter and Kirk Perris of the Commonwealth of Learning presents three examples of partnership and collaboration types drawn from the academic and business literature. Four case studies of partnerships and collaborations are then presented, and the aforementioned types are applied as a best fit to a given case study.

The three types of partnership are:

- propositional collaborations: an example in higher education is the branch campus, set up in a less advanced economically developed country by an institution in a developed country;

- cooperative: these are partnerships where participating institutions have equal status: all stakeholders participate in a democratic decision-making process to ensure outcomes are truly congruent with the majority’s needs;

- mutual service alliances: participants engage in an arrangement that provides content, service, and support at a lower cost or with lower overhead than what might be expected participating in the same service as a singular entity.

The authors then provide four examples of collaborations and partnerships in practice:

- the Commonwealth of Learning’s Regional Centres

- the Partnership for Enhanced and Blended Learning among a collection of universities located in four East African states, with support from the Commonwealth of Learning, the Association of Commonwealth Universities, the University of Edinburgh, and the Staff Educational Development Association, with project funding from the U.K. Department for International Development

- BCcampus, British Columbia, Canada

- eCampus Ontario, Canada

The authors then classified these four examples in terms of the three types of partnership. The authors conclude: Partnerships are contextual….Any view to sustainability must recognize partnerships as dynamic, subject to change, and not necessarily bound by fixed deliverables, time frames, or resources.

Although each of the cases is interesting in its own right, I share the author’s conclusion. Partnerships can be very valuable, but each depends on often a unique mix of circumstances and are dependent on people of goodwill able to work together for a mutual benefit.

36. Marketing Online and Distance Education, pp. 605-621

This chapter, by Maxim Jean-Louis of Contact North, Ontario, Canada, explores contemporary approaches to marketing online courses and programs. The chapter is basically in five parts:

- introduction: understanding context, particularly that of online and distance education;

- changes over time: the online and DE market has changed considerably over the last 50 years: the challenges faced have been different and each phase has demanded a different marketing response;

- the process of marketing online and distance education services, including:

- building the brand story: differentiation

- target marketing and market segmentation

- mining niche markets and services

- focus on retention and not just attraction

- using data systems to track return on marketing investment

persistent issues/myths to overcome:

-

-

- ‘face-to-face is best’

- ‘the loneliness of the long distance learner’

- ‘online is cheaper’

- ‘it is easier to cheat online’;

-

- overall conclusion

Anyone with responsibility for online programs will benefit from this chapter. It is far more than a general marketing paper, but instead focuses on the specifics of marketing online programs.

Maxim Jean-Louis makes the critical point that the best marketing tool for online/distance programs is program success:

- high completion rates (retention is more important for enrolments than recruitment);

- students feeling supported by the instructors and the institution;

- valid qualifications that result in students achieving their learning goals, whether they are a new career, a better job, or satisfying a burning interest.

These are the factors that enable successful marketing.

37. Managing innovation in teaching in ODDE, pp. 623-640

This chapter is a bit difficult to review objectively, as I (Tony Bates) wrote it. But here goes:

I argue that: Innovation is the lifeblood of open, distance and digital education (ODDE), but it has often proved difficult for ODDE institutions to continue to innovate in response to a changing world outside. Innovation though is not “magic” or serendipitous. There are well-established methods by which innovation can be nurtured and managed in ODDE.

Innovation is essential for ODDE

The chapter opens by arguing that innovation is the lifeblood of ODDE – without it, it cannot compete with ‘traditional’ education. There are at least five drivers of innovation in ODDE:

- its dependence on technology, which is constantly changing;

- its aim to reduce costs, either to students or government;

- its aim to widen access to groups beyond the traditional higher education market;

- the need to reduce or eliminate inequalities to access resulting from technology innovation;

- the need to respond to the changing educational demands of a digital age.

This means innovation is needed not only in delivery methods but also in teaching and learning.

Resistance to innovation in ODDE institutions

I also argue that the innovation has proven to be difficult for many ODDE institutions, once established, for the following reasons:

- all institutions tend over time to revert to hierarchical structures geared toward rewarding compliance rather than change;

- ODDE institutions often have heavy investments in initial technology that make adoption of new technology either peripheral or impossible;

- the Internet reduced the cost of course production and delivery, enabling dual mode institutions (mainly campus-based universities with small ODDE offerings) to move more quickly to innovative teaching than dedicated open universities.

Five myths about innovation

I then draw on Morriss-Olson’s five common myths about innovation:

- innovation is difficult

- innovation ‘just happens’

- innovation works best in skunk-works

- innovation needs creative geniuses

- innovation is always good.

Barriers to innovation

The following can be barriers to innovation in teaching:

- lack of effective leadership (a lack of recognition that ongoing innovation in teaching is necessary);

- existing organizational structures and culture: compliance rather than change;

- lack of systematic training in teaching which is required to enable innovative teaching;

- incompetent middle management due to lack of knowledge about educational technology’s strengths and weaknesses;

- lack of resources to support innovative practices (priority goes to existing practice).

Strategies to support innovation

- an holistic approach to innovation in teaching across institutional boundaries;

- innovation embedded within annual academic plans for teaching and learning;

- funding earmarked for innovation in teaching.

A case study

The article looks at the systematic approach of the University of British Columbia to innovation in technology-based learning over a period of 25 years, illustrating how different strategies supporting innovation in teaching and learning were applied.

Can you ‘manage’ innovation?

There is a certain serendipity about innovation. Consequently I argue that the focus should probably not be on innovation itself, but on the educational goals, such as increasing access and equity, that an ODDE organization is aiming to achieve. Innovation would be one means by which to achieve such goals.

Change or die

The chapter ends with a discussion about the potential competition that ODDE institutions will face, particularly from the large digital technology companies. This means that ODDE institutions will need to have relevant, challenging strategic goals that move the institution forward. This is what should drive innovation. Innovation is a means to an end: more relevant, high quality education for those learners most disadvantaged and not well served by the traditional system or other external competitors. More of the same will not do.

In conclusion I thought this was an interesting and provocative chapter – but then if I didn’t, who would?

38. Transforming conventional education through ODDE

The last two chapters are from authors in the antipodes.

The chapter by Mark Nichols, of the Open Polytechnic of New Zealand, explores the differences across educational models beneath the terms “conventional education” and “open, distance digital education (ODDE),” and the nature of “transformation” as conventional and distance models of education are expressed online. The potential of ODDE ……goes well beyond extending the classroom into the online space. For on-campus providers to become effective ODDE providers, a transformation is required.

Nicholls argues that ODDE is not achieved merely by moving campus-based models of teaching online, as happened during the Covid-19 pandemic. Nichols argues that institutional transformation is required to become an effective provider of ODDE.

Nichols takes aim at equating synchronous delivery of lectures by video-streaming with online distance education, because there has been no ‘transformation’ of teaching methods, organization, or practices, merely a change of delivery. However, there has to be a more comprehensive ‘transformation’ necessary for effective ODDE.

Nichols then goes on to examine the differences or distinctions between conventional education and ODDE, and the nature of educational transformation, drawing particularly on the R.A.T. and SAMR models of transformation in teaching and learning. True transformation requires more than just a change in teaching practices; it also requires fundamental re-organization of the institution to support such change. He goes so far as to argue that Conventional education is different to ODDE to the extent that they are operationally incompatible.

Nichols then goes on to argue that higher education has been remarkably unchanged by the disruptive elements of the digital revolution. More challengingly, he then goes on to argue that The potential of digital education to provide a quality robust, accessible, cost-effective, flexible, scalable, supported, and personalized education…..cannot be fully realized by the conventional education model. He then discusses why conventional education has failed to transform to the realities of a digital world (basically, because it is too hard for conventional institutions to do). He then discusses a five year plan for possible transformation, using as an example the UK Open University.

He concludes that Conventional education providers seeking to realize ODDE benefits, then, must anticipate transformation of their operating models…Without a deliberate redesign of the underlying operating model of education, “going online” results in transfer of practice rather than transformation.

This is a highly provocative chapter. It assumes a hard distinction between synchronous, in-person learning, and effective ODDE, and implicitly argues that ODDE is the more suitable model, having ‘transformed’ to accommodate the digital reality of the 21st century.

However, the reality is that, at least in most North American (and antipodean) universities and colleges, conventional and ODDE programs exist side by side. Thus the chapter takes no account of what used to be called dual-mode institutions, who operate successful on-campus and distance programs. Campus-based programs usually serve a different target group from the on-line programs.

Sure, campus-based institutions need to change and adapt, but I just don’t see the need for conventional institutions to ‘transform’ entirely to an ODDE model, as Nichols argues. Many students (and parents) still want the on-campus, in-person experience. Indeed I see as much need for older ODDE institutions to transform as conventional HE institutions.

Also, I see much more blurring of boundaries as a result of digitalization of teaching, with a continuum from fully in-person through blended and hybrid to fully online, depending on both the needs of students and the requirements of the subject matter. But I agree with Nichols that such changes need to be transformational to be successful, whether for conventional or ODDE institutions.

39. Academic Professional Development to Support Mixed Modalities, pp. 658-675

This final chapter in this section, by Belinda Tynan, of Deloitte, Melbourne, Australia, Carina Bossu, of the Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, and Shona Leitch, of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, explore(s) professional development (PD) of academic and teaching staff in the use of technologies to support learning in mixed modalities, including blended and online modalities in higher education contexts. The authors…explore current practices in both face-to-face (f2f) and online/distance education contexts.

The chapter starts with an exploration of the impact of Covid-19 on professional development, as the world of higher education switched to online delivery. The authors note that prior to Covid, much of the provision [of professional development for teaching] is accessed by a small number of academic staff who are interested in learning and teaching, and often those who need the support the most do not engage with such opportunity for support and upskilling….[but] something changed during COVID. Across the globe, there were reports that universities had thousands of their staff sign up for PD. They needed to know how to teach online.

The authors then provide an overview of the literature on academic professional development in general, drawing lessons for PD from each source.

They then provide the following cases to identify different approaches to academic development for online teaching:

- the UK Open University’s Applaud program for its own academic staff leading to national accreditation ny the Higher Education Authority

- RMIT’s initiative to provide ‘just-in-time’ PD on teaching online during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The authors come to the following conclusions:

- There is no doubt that there is a complexity when it comes to supporting academic staff in their ongoing PD as teachers and pedagogues

- it was evident during COVID-19 as many universities moved into remote and online teaching that new skills were required

- The online environment has unique challenges that require a deep understanding of how students learn in this mode.

- As more universities shift into blended and online modalities, workload is another key consideration

- There is no fixed approach or one solution that can be applied globally to PD in an institution.

The chapter then ends with a set of eight recommendations.

I don’t think those already working in professional development, especially regarding blended and/or online learning, will disagree with most of the points made in this article. It is a fairly comprehensive discussion of best practices in this area, and will certainly be useful for managers or administrators unfamiliar with the need for professional development for those moving into blended and online learning for the first time.

However, the article did not really deal with the challenge of organizational and academic culture, where PD is a voluntary activity and can be safely ignored by instructors who do not wish to participate. It is my view that specific training in teaching, including the specific requirements of blended and online learning, should be required of all instructors, for quality reasons. The real challenge then is how to change the organizational culture so that such a radical change becomes acceptable.

Overall review of Part IV

This overall review covering my two posts on this section of the book, i.e. Chapters 28 to 39, is posted separately, because this post is already too long. You can find it here: https://www.tonybates.ca/?p=12578

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.