Farmer, H. (2020) 6 Models for Blended Synchronous and Asynchronous Online Course Delivery, EDUCAUSE Review, 18 August

Multiple models

I have argued elsewhere that blended learning is likely to become the default model for most higher education teaching post-Covid. But what does that mean?

There are many different models emerging, to name just some:

- Technology-enhanced classroom learning (face-to-face classes supported by Powerpoint, or clickers, or active classrooms, or augmented or virtual reality)

- Face-to-face (lectures) + the use of an LMS for supporting face-to-face teaching

- Live face-to-face classes while simultaneously streaming the lesson to those off campus (or at least, outside the classroom): see here for an example

- Live face-to-face classes with the recording available on demand

- Flipped: streamed video + a follow-up face-to-face session (or the opposite: a face-to-face session followed by online work/discussion): see here for an example

- One semester on-campus; two semesters online (the Royal Roads University model)

- Hybrid: reduced face-to-face time + online learning (preferably with an intention of getting the best from each through a specific course design)

- HyFlex: one course accessible in any combination, depending on the need of individual students: see here for an example.

I am sure that there are other variants on these different models.

Another variable that cuts across all these models is the balance between synchronous and asynchronous teaching, given that face-to-face teaching is primarily synchronous, but online learning can be both.

Blended learning is also a conceptual mess at the moment, mixing up modes of delivery with different pedagogical approaches (deliberate in a few cases, but mainly accidental in most, in the sense of trying to convert a face-to-face declarative model of teaching to online learning.)

What we can agree on is that this is a very dynamic situation, with new combinations of face-to-face and online emerging all the time, which makes definition if not futile, at least almost impossible.

In other words, this is an ideal situation where a little theory could go a long way in bringing some sense or understanding of the potential benefits or drawbacks of the different emerging models of blended learning. Hence I give a huge welcome to Heather Farmer’s paper. Heather works at Sheridan College, in Ontario.

Guiding principles

There are several guiding principles behind the six models developed by Heather Farmer.

- The different affordances of face-to-face and online teaching (what each does best)

- The different affordances of synchronous and asynchronous learning

- The relative autonomy of different learners, and in particular the degree to which a learner is ready or able to take responsibility for their own learning; this in turn depends on the level of support that students receive from instructors and the institution.

The six models

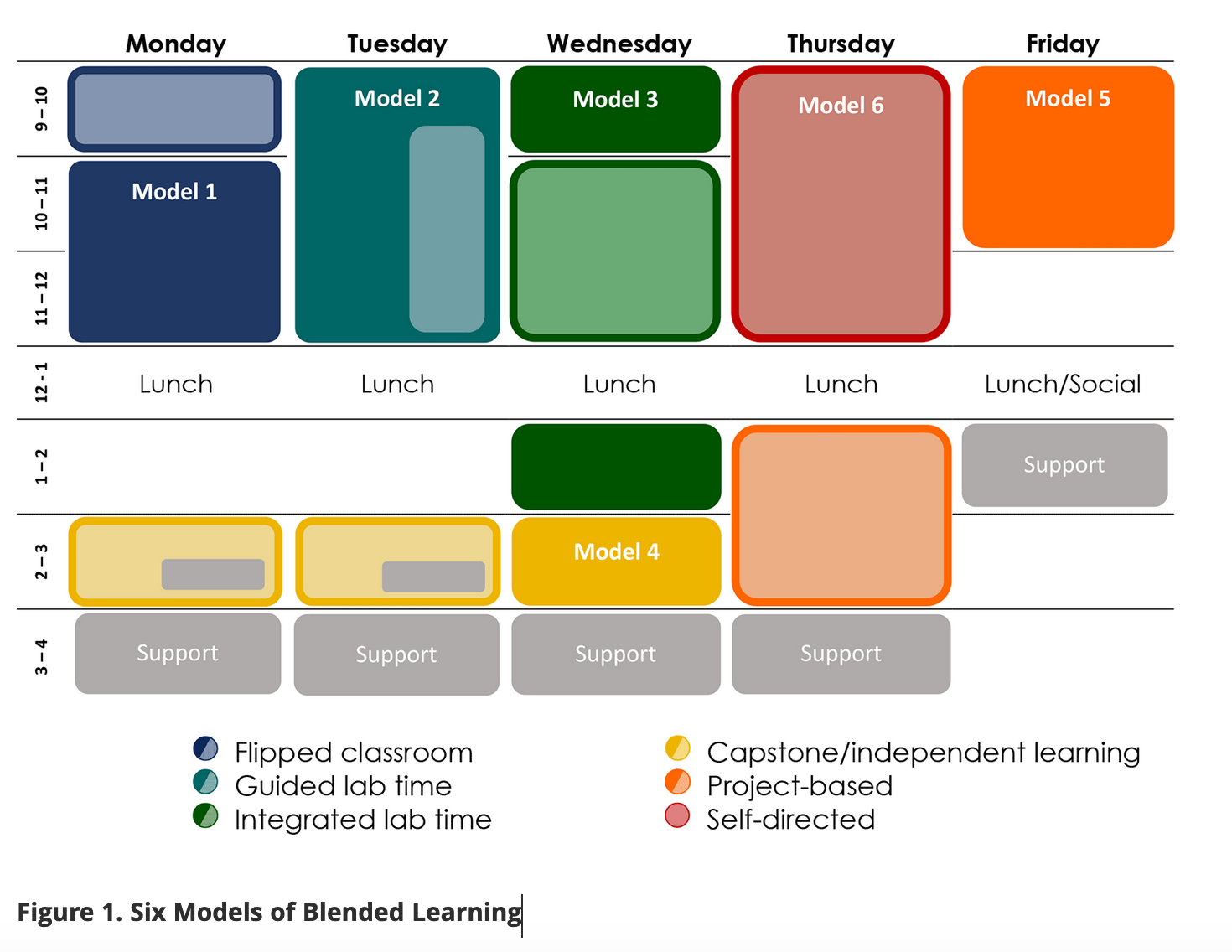

The models range from a highly supported and faculty-guided model to an independent, self-paced model:

- flipped classroom;

- guided lab time;

- integrated lab time;

- capstone/independent learning;

- project-based; and

- self-directed.

You need to read the full article for more details on each of these models.

A good start, but more is needed

I fully agree with Heather Farmer’s statement that:

faculty need to take the time to consider which online blended model best aligns with the needs of the learner and the learning outcomes of the course. Once the model has been selected, sharing the rationale with students and explaining how the strategies support the curriculum will help them better understand why part of the course is being delivered synchronously and part of the course is being delivered asynchronously, what the purpose and role of asynchronous learning is in the course, and how the asynchronous learning fits into the overall lesson plan.

I particularly like the recognition that students vary considerably in their learning autonomy. The models also take account of the need to manage the time students spend on activities, so they are not overloaded with both face-to-face and online work.

However, I was disappointed to see that Farmer has defined the models in terms of a three-hour credit model, presumably so that each model ‘fits’ within a campus-based timetable. I understand the practicality of this, but it is still trying to fit a digital teaching strategy into an industrial organisational model. As we move to more blended and digital learning, we need to re-think the current organisational model of fixed time-and-place lessons, as well as the spaces on (and off) campus that can best support the asynchronous component.

One of the benefits of asynchronous learning is that students have more flexibility of not only when they study, but how and where. For instance they may want to spend more time online than in class, in order to master content or practice skills. Many students study online on the bus to campus, or in random moments of spare time, such as waiting at the dentist’s. One touted advantage of blended learning is that the outcomes are better because students spend more time on task. In particular, instructors should consider what the most appropriate mix of synchronous and asynchronous learning would be for learning outcomes such as skills development. Can online learning be used to increase the time spent practising, for instance? Also, in any one class, there is likely to be a mix of learners’ autonomy, so such a timetabled model won’t fit all students.

Thus Farmer’s six models are restricted as much by organisational requirements as by learner autonomy. Nevertheless, using a theoretical construct such as learner autonomy is exactly the right approach to discussing the benefits and limitations of blended learning, and how best to design it. Design needs to be embedded in theories of how students best learn and the affordances of synchronous and asynchronous learning, but we also need to look at better ways of organising our campuses so that asynchronous learning can be more easily accommodated, both on and off campus.

In the meantime, if you are at all interested in blended learning, please read Heather’s paper.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Heather Farmer comments:

I agree that timetabling asynchronous time is constricting. However the visual is more or less an organizer to illustrate how the time could be broken up.

In fact, when using that visual in workshops I point out that the asynchronous time in models 3-6 could be done at any time. For example, the visual for Model 3 was strategic, those learners that are quick to task might wrap up early and get a long lunch, while the ones who need more time on task might work into or through lunch. But regardless of how varied the abilities may be in a given class, they might all be given the opportunity to finish before they reconvene after lunch.