Murgatroyd, S. (2021) The precarious futures for online learning Revista Paraguaya de Educación a Distancia, FACEN-UNA, Vol. 2, No. 2

Stephen Murgatroyd is a big picture kind of guy. He likes to observes trends, then make not so much predictions but dire warnings about our febrile hopes and optimism regarding the power of educational technology in managing the challenges of the future – a Nostradamus for 21st century online learning. Stephen is a welcome antidote to the hype and hysteria of the media and educational gurus who believe the pandemic will force radical change, and online and digital learning will come, like the cavalry, to the rescue.

Stephen’s argument

In this article he does a great job of analysing the shifting ‘systems dynamics’ of higher education and the likely drivers of higher education policy post-pandemic. It makes for depressing reading but I ain’t saying he’s wrong.

Then he critiques the notion that technology will transform and ‘save’ the futures of universities and colleges. He is deeply sceptical that this will be so, and examines the underlying barriers to the transformation of higher education through digital technologies. Again, I don’t disagree with his analysis of the barriers and the challenges they present.

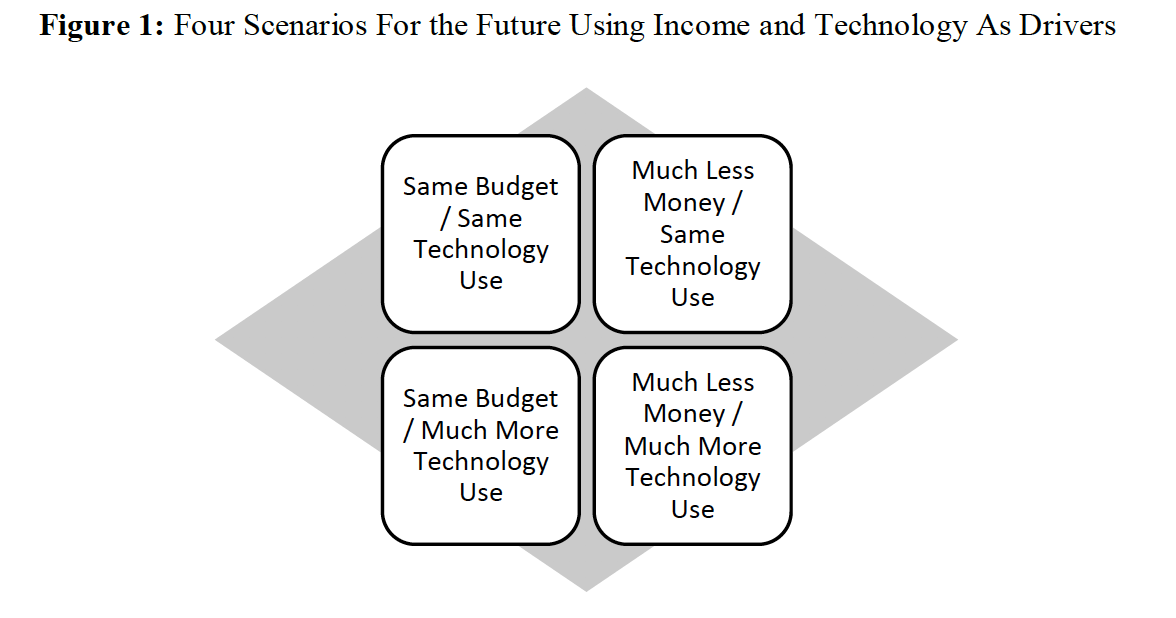

He ends by offering four pretty generalised scenarios based around two dimensions: finance and technology (see diagram below).

While I agree that universities and colleges will continue to face major financial issues in the future, I’m puzzled why the scenarios are based on only two dimensions, when there are other possible dimensions – such as political will and ideology – that could influence future scenarios. But it does simplify the issue down to four possible outcomes. What is not clear is the degree of choice institutions will have between these scenarios.

My response

And that’s the problem of projecting into the future. As the old Yiddish proverb says, ‘When Man plans, God laughs.’ Murgatroyd’s views can be seen either as coldy realistic or unjustly pessimistic.The future may still turn out differently, and that is because people and institutions adapt and adjust to external conditions, and thereby to some extent influence the external factors – it’s not a one way system.

As I said, I agree with his analysis in general – I just think he’s too pessimistic. I see steady if less spectacular progress being made in the integration of digital technology into higher education teaching. For instance, in Canada in 2019 (CDLRA, 2019):

- 75% of all universities and colleges offered at least some online courses,

- somewhere between 10-15% of all credit course enrolments are now in online

- online enrolments were steadily increasing by 10 per cent per annum up to the pandemic

- virtually all institutions are now using LMS and video conferencing technologies

- the majority of institutions viewed online learning as strategically important

- 71% of institutions had implemented or were in the process of implementing an eLearning strategic plan.

The pandemic will not have slowed any of this down – indeed it has increased the intensity and pressure to move forward:

- one institution in which I am working had already secured substantial internal funding pre-pandemic to support the implementation of its eLearning strategy. The strategy was boosted during the pandemic because a much larger number of faculty requested faculty development opportunities than anticipated and because the value of the instructional and web designers became obvious when everyone had to switch to emergency remote learning;

- Ryerson University’s School of Continuing Studies will not be returning to on-campus classes, but will offer all its programs online this year. (Ryerson is an inner-city university in Toronto, but its Continuing Studies students come from across a wide geographical area).

- Laval University, a campus-based francophone university in Québec, has now more online course enrolments than either of the two open universities in Canada, Téluq (francophone) and Athabasca (anglophone)

- universities and colleges are increasingly integrating digital technology into campus-based teaching through blended learning, flipped and hyflex classes. The numbers are small at the moment but again growing steadily each year.

So I see a middle road between the over-exuberance and over-selling by media pundits and education gurus of educational technology and particularly artificial intelligence, and Stephen’s dystopian future for higher education. I agree that the slow and steady progress in digital learning may still not be enough to avoid the collapse of at least public higher education – but let’s give it a chance. In the meantime, read Stephen’s article in full – it’s an enjoyable read.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Tony

Many thanks for drawing attention to this paper, which is receiving a lot of traction. It builds on a contribution I made to an edited collection of papers Radical Solutions for an Education in a Crisis Context (Burgos, Tlili, Topbacco 2021) and to my teaching at the Universites of Toronto and Alberta.

A few minor points:

1. You ask why only two dimensions? This is how scenarios are usually developed. Finance is a proxy for a variety of things – public policy, ideology etc. It is also what drives a great many decisions at the systems level. As someone who lives in Alberta, political will here is also about privatization and commercialization of public good, hence the deep cuts to university budgets.

2. You give examples and instances of innovation and change, which I also see. But these are pockets and a collection of pockets do not make for a really great suit! Having worked (and continuing to do so) globally, I look to places like The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand for inspiration and innovation. I can point to a great many pockets of innovation. But I am more interested in the broader patterns.

I also based some of this thinking on working with literally hundreds of faculty in a variety of institutions – work I summarized in another paper in the same journal (Revista Paraguaya de Educación a Distancia, FACEN-UNA, Vol. 1 (2) – 2020 – http://www.facen.una.py/es/reped-2/) and to some of the horrific stories of online learning shared with me by students. For each good news story, it seems to me there are least 2 bad news stories.

What is also interesting, to me as a futurist, is the emergence of an agenda to leverage both ODFL and micro-credentials as a means of transforming universities in particular. Several government Ministers I have worked with within the last 2-3 years see universities as permanently failing organizations that need to change, not that they have any real idea of what a university is, could be or how it could change. Indeed, one Minister said explicitly that “I see these new credentials as the beginning of the end of the degree” (it was also the beginning of the end of his stint as Minister!).

I do not buy the transformation conversation (I wrote about this too is the same journal – http://www.facen.una.py/es/reped-ano-1-numero-1-enero-2020/ – and I think the Gartner Hype Curve should be on the wall of every university and college President. But I also don’t see a lot of courageous, transformative leadership in our universities. Indeed, one of my major concerns as a consultant watching the meander towards the future is the lack of determination by Presidents and their top teams around purpose and the degree of their entrapment in systems no longer fit for purpose – quality assurance, funding models, models of faculty hiring and promotion, tenure etc. It is difficult to find leadership and for leaders to act boldly when fear and inertia are the components of their day-to-day. There are exceptions, of course, and we all cherish them. But look at the big picture – it is not pretty.

Back in 1974 I wrote a Fabian Society pamphlet (with Stephen Thomas) on Education Beyond School (followed by a pamphlet for the Independent Labour Party with David Reynolds on similar themes) and suggested then that the core challenge for the future of universities was a relentless and focused commitment to a broad purpose. Some had lost the plot even then, and others are now struggling to define and focus on purpose. That is my core point. All else follows.

There are some wonderful examples of exemplary teaching and learning out there – we should celebrate and share them, but my paper is more about the bigger picture and socio-political-technological context.

Stephen

Stephen, you make many interesting points in both articles and I recognise many of them and like Tony agree with many but not necessarily the conclusions. Your main premise is that the HE sector needs to change and yet the hype around technology enabled learning caused by its prominence in discourse due to the pandemic is not the driver needed for change. I agree, but the again I found some of your arguments to then focus on the transformation of individual institutions in the light of global changes, many of which are driven by the pandemic. You also, rightly in my view highlight what governments are thinking and doing and the influence they have but then above you note the ‘lack of determination by Presidents and their top teams around purpose and the degree of their entrapment in systems no longer fit for purpose – quality assurance, funding models, models of faculty hiring and promotion, tenure etc.’. It is here where I particularly part company with your arguments. I feel that it the legal, political and social licence (=trust) to operate that is the major factors shaping the HE sector. In some countries HEIs have no autonomy – they are public institutions – and most ‘open universities’ are state born entities. Even in countries where there is a thriving private HE sector there are many rules and expectations that HEIs have to pay attention to. ODFL is often more regulated or has more issues of social trust to deal with than campus based learning. I also think that a significant issue is that public and political interest in HE is low most of the time except when folk actually have to engage with HE. And lastly most HEIs are very place based, few undertake significant TNE by operating in more than one country and most only collaborate with other HEIs in limited ways and rarely in a coordinated way to drive sector wide change themselves. So my bigger picture is for HEIs to think global but act local and go for evolutionary not revolutionary change.

Thanks, Andy. The main threat I think to public universities is not their lack of innovation – although it is one factor – but shifting ideologies and markets, particularly regarding the role of the private sector in providing alternative offerings that are more attractive to potential students, mainly because they are cheaper and more immediately job-focused. However this will affect more the community college sector and the less prestigious, smaller universities.

I agree with you that there is still a large degree of trust (maybe misplaced) in the more prestigious universities that allows them to change in a more sustainable and less threatening manner. However didn’t someone say trust is hard won but easily lost? (No, that was reputation – sorry, Shakespeare)

Nice commentary! I chuckled (sadly) at this: “But I also don’t see a lot of courageous, transformative leadership in our universities.” That’s always been pretty rare, IMHO. Real transformative leadership isn’t always rewarded and may even be punished (maybe too strong a term). This seems to be the case even when boards of regents or trustees say that’s what they’re looking for.

That said, I am cautiously optimistic that the emergency remote instruction we saw over the past 18 months may lead to improved instruction and outcomes not only for online learning but also on campus. Call me an optimist, I suppose. After many years in faculty development, I know that most professors want to be good teachers and many want to be even better teachers. If that can become an institutional imperative, at some point, I’d like to think it could influence policy/decision-making.

At a recent conference, I noted that those of us who’ve worked in educational technology and distance ed since before the advent of the internet, in many cases, must refrain from saying, “I told you so.” In too many cases our voices have been drowned out by calls for superficial innovation that simply tosses the latest disruptive (ugh) high-tech device into the mix without looking at what actually improves learning outcomes. Still, I remain hopeful with a side order of reality.

Many thanks, Susan, for a great comment

Nice Article. Thanks for sharing with us.respectable facts for another blogger… it is in reality useful,