Bartolic, S. and Guppy, N. (2021) UBC’s Pivot to Emergency Remote Teaching and Learning: Perspectives on the Transition at the Vancouver Campus Vancouver BC: University of British Columbia

About the report

The University of British Columbia is one of Canada’s most prestigious universities, usually in the top 30 of global university rankings. It is also big, with over 66,000 students at its Vancouver campus and another 9,000 at its Okanagan campus in Kelowna.

I also worked there for eight years between 1995 and 2003 as Director of Distance Education and Technology, assisting the university in developing online courses and programs. One of the authors of this article was at the time UBC’s AVP Teaching and Learning to whom I indirectly reported, and the other author I initially hired as a researcher, but is now a professor in the department of sociology – so there’s my declaration of interest.

Nevertheless nearly 20 years has given me a somewhat different and distant perspective. I found this report a fascinating account of the actual pivot in March 2020. This article is required reading for anyone interested in the nuts and bolts of how a large university responded to the switch from mainly on-campus teaching to entirely online teaching due to Covid-19. For this reason I am adding it to my Research reports on Covid-19 and emergency remote learning/online learning but I give a more detailed analysis below.

Methodology

UBC pivoted from face to face teaching to emergency remote instruction in almost all classes. The official announcement on Friday, March 13, spoke of a “shift in delivery” as the university “transition[ed] to online classes effective Monday March 16, 2020.”

Evidence was gathered in the following ways:

- Faculty — interviews with 57 faculty members in five Departments (response rate 54%), with supplementary self-administered questionnaires from 53 faculty members

- Students — self-administered questionnaires returned by 1,069 students enrolled in the courses of those faculty members interviewed (response rate 46.5%), and 138 questionnaires returned by students who were in courses where faculty members were unable to be interviewed

- Learning support specialists — interviews with eight instructional design professionals

- Senior administrators — interviews with 12 people in key decision-making roles in the Provosts Office, the VP Students Office, and three Dean’s offices

- Learning Analytics — data connected with 100 courses that were sampled, data that features tool activation, distinct Canvas sessions, and other measures of online activity, were collected and analysed

- Registrar’s Office — data on course enrolments and class composition, and data on academic concessions granted to students

The UBC researchers began interviews with faculty members in early May 2020 and completed the majority of them by mid-June. Similarly student questionnaires were distributed mainly in May 2020. It should be noted then that these responses reflect initial reactions within two months of the pivot.

The authors quite rightly point out that this is just one perspective or analysis of an experience that will have varied tremendously between different actors. The focus is on just five departments (Chemistry, Civil Engineering, History, Political Science, Psychology).

Appendix 1 of the report provides a detailed description of the methodology used.

Main results

As always, this is my personal interpretation. Please read the full report for more detailed and nuanced findings

1. Emergency remote teaching – not courses designed from the outset as online learning

The authors point out:

While the pivot to remote teaching and learning can be described as a transition ‘to online classes,’ as did UBC on March 13, a more appropriate phrasing for the mid-March shift might be ‘emergency remote teaching’ or even ‘improvised instruction.’

The latter two phrases more carefully capture what faculty reported doing, what students say they experienced, and what instructional design professionals and administrators faced.

Furthermore, the idea of ‘remote instruction’ separates what UBC did in a large majority of courses in Term 2 from those courses that were already using robust, fully online delivery from the Term’s outset. The differences between these two forms of instruction are substantial.

2. A leap into the dark for most faculty – and students

Faculty responsible for delivering content were desperate for know-how, tools, and directions. In part, though, there may have also been an assumption that students were more capable of mastering a digitally-enhanced world of virtual learning than were faculty of building and delivering it.

3. Rapid and comprehensive change is possible even in a large university

Universities, especially large, established ones like UBC-V, are often caricatured as ponderous, slow bureaucratic dinosaurs. Moving thousands of courses online within a few days shows a nimbleness, and a preparedness, few would have anticipated. People felt proud when individual efforts fused collaboratively to create major social change.

4. Academic policies and integrity under stress

The pandemic made old rules precarious – on academic progression, course withdrawals, and grade allocations – and we were nearing the end of a term. In the face of widespread uncertainty about their educational careers, students were presented with a series of newly crafted options that allowed them to make reasonable choices about how to continue their learning, or not. It might be hard to overemphasize how important this was to students’ immediate well-being, but also to their ability to plan for the future, short and long term (and is probably reflected in strong summer and fall enrolments)

The details provided about how the university dealt with these issues will be of particular interest to those concerned about academic integrity and the ‘quality’ of the learning experience during the emergency, and the changes or tweaks to policy that were necessary to enable students to cope under pressure. In particular, the report analysed specific changes to:

- Credit/D/Fail practices

- Course withdrawals

- Deferred standing

- Final exam practices

Academic concession options were expanded. No new concession policies were devised but existing ones were significantly adapted to permit greater discretion in their application. This effectively meant offering options to the entire student body that would ordinarily only have been available to students facing extraordinary personal circumstances. Academic practices changed, academic policies did not.

Effective communication was a major challenge

Communicating coherently about COVID-19 communications at UBC-V is near impossible!

As a fairly decentralized organization, especially when it comes to teaching and learning, communicating to everyone with a uniform voice, and message, is extremely difficult. Multiple message-managers (UBC admin; instructors; government health officials) made crafting difficult, approval complex, and timing complicated.

Nearly all classes were shifted online

95% of UBC-V undergraduate credit classes were able to make this transition. Teaching did not stop and most students were able to complete their courses. Few classes were cancelled. Most faculty members reported already utilizing UBC-V’s Learning Management System (LMS) as a teaching resource before the switch to emergency remote learning.

While the disruption was major, the integrity of the academic term was maintained, with some compromises having to be made. Furthermore, the vast majority of courses still held a final examination (71%), and in most of these cases it was mandatory as opposed to optional.

The transition worked well

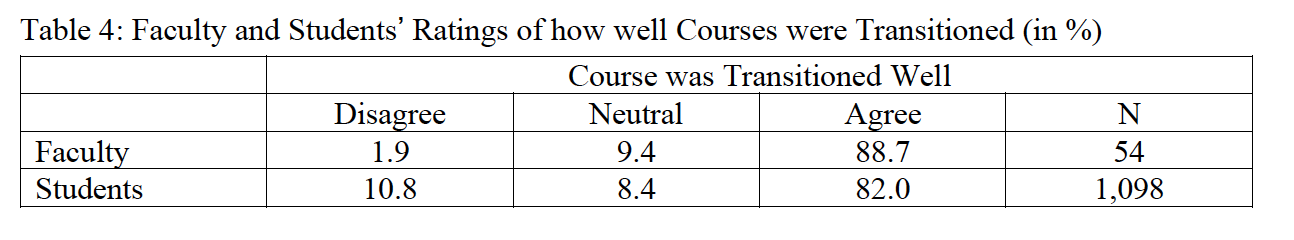

Both students and faculty thought that the transition to emergency remote teaching went well, as can be seen from Table 4 from the report.

This finding was reinforced from an examination of Student Evaluation of Teaching (SOeT) reports for the same semester in 2019 and 2020.

Communicating after the pivot was crucial to the success noted above. When faculty were asked to report on how often they communicated with students, the majority reported they were sending messages to students at least two or three times a week (over 70%).

Other findings

There are interesting sections also on:

- academic integrity

- student well-being

- the future of online courses ( a very mixed response)

Main conclusions of the report

- the transition went much more smoothly than many might have anticipated. Certainly the signals of successful course transitions are many

- collaboration was critical – not just between faculty and students, but also with the many staff in many departments that supported the transition

- nevertheless, the quality of the learning experience was judged by most faculty and students as low. Our evidence shows that students in stressful living circumstances were especially likely to feel that their learning was compromised

- UBC-V was fortunate to have had a relatively high level of learning technology already in use prior to the pandemic’s onset.

- decentralisation of decision-making was critical to the success of the transition

- the future of e-learning remains as contested as ever. Most students and faculty recognized that the COVID-19 pivot was not a reasonable way to judge the costs and benefits of learning on digital platforms. Clearly more students and faculty have developed capabilities to make effective use of e-learning tools than was the case prior to March 2020.

My comments

I think this report will be useful to two quite different audiences: those looking for guidelines about how to handle future emergencies in higher education; and especially for historians who are interested in exactly what happened in universities during the pandemic. It is important to have the experience documented as accurately as possible, and this is a pretty convincing account of what happened in the early months of the pandemic at UBC.

The study did emphasise for me the somewhat arcane academic policies that influence or guide student progression through a university program, and the pressure to find ways to quantify what is essentially a qualitative process – ensuring academic value under the pressure of extremely abnormal circumstances.

In this sense, there is a good deal of hubris in the report that is typical of elite universities. I don’t think anyone would be shocked that learning was to some extent negatively impacted during an emergency, even – or especially – in an elite university. At the same time, the enormous effort and the achievement of moving all teaching online and completing the semester justly needs to be recognised.

The report also focused only on the early part of the pivot. It will be interesting to see if the results are different after a year, where lessons will have been learned and applied – or maybe not. Overall, a highly recommended read for anyone interested in the nuts and bolts of university administration during an emergency.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.