This is the first of 10 Lessons from a Post-Pandemic World. For the other nine, click here.

“…in blended learning, student performance improves over both face-to-face and fully online learning.”

Before COVID-19, research indicated that in Canada, faculty resistance was a main barrier to increased online learning. In March and April 2020, however, all instructors had to move to at least emergency online learning. That was a cathartic moment.

The experience clearly varied. Some instructors took to it like a duck to water. Some hated it and still do. But the majority, who reluctantly did what they had to and were not completely happy with it, also learned there is much that can be taught online just as well if not better than on campus.

And many learned that online teaching, especially working from home, can be very satisfying, as well as convenient.

Accelerated growth

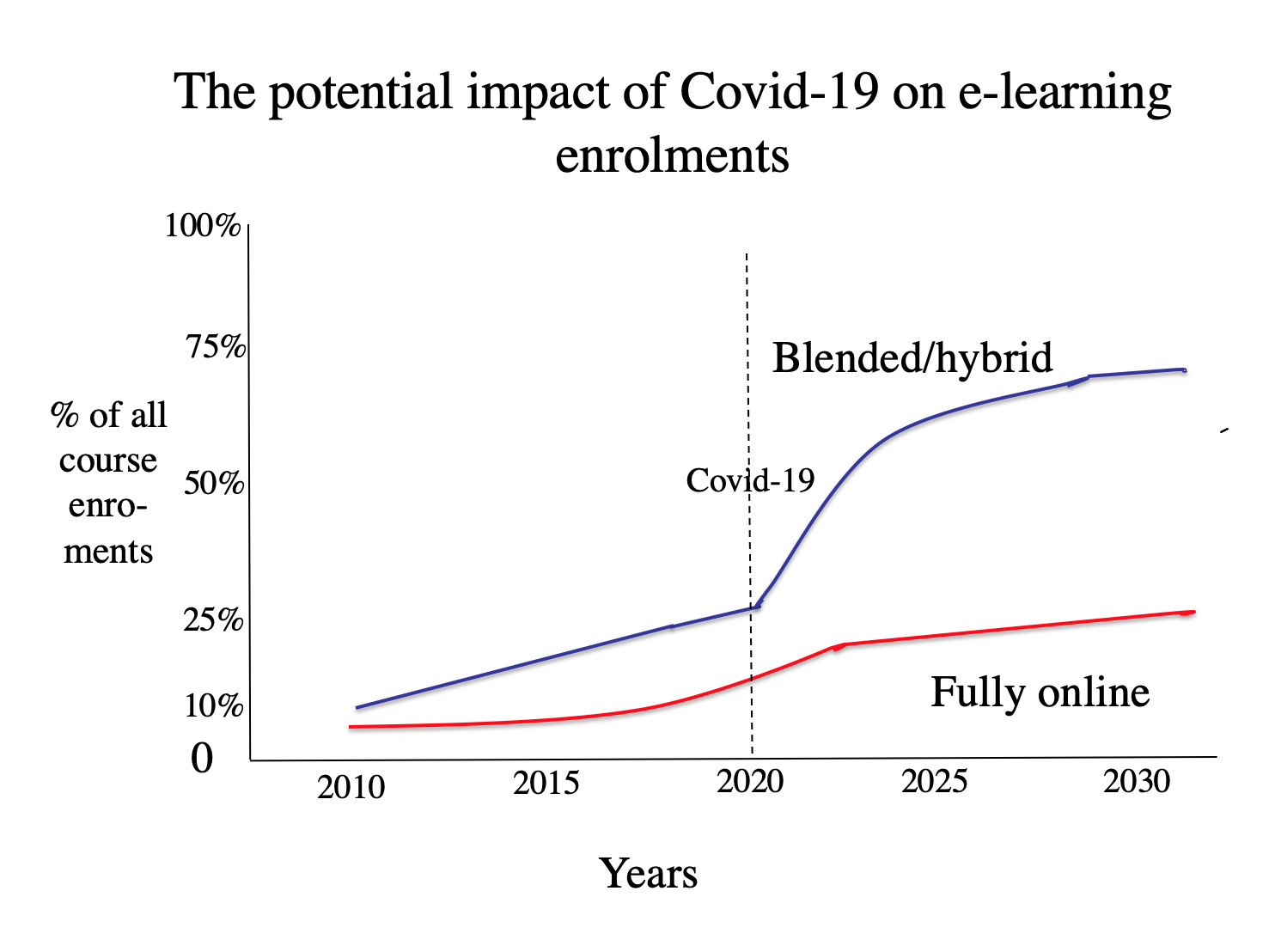

In fact, before 2020, fully online learning was increasing steadily at a rate of 10 per cent a year in Canadian colleges and universities, until in 2018 it constituted 10 per cent of all credit course enrolments (see Johnson, 2019).

I expect that after COVID-19, there will be an up-tick overall in the number of fully online courses and enrolments in these courses. Courses successfully moved online during COVID-19 are likely to stay online if there is sufficient demand from students.

However, we know that fully online courses appeal more to older, working students, and hence more to post-graduate or continuing education students, or students in their final undergraduate year.

I anticipate then that fully online learning will not increase to more than 20-25% of all credit course enrolments.

In contrast, though, I see a rapid and massive move to blended learning, where students mix campus-based and online learning (see Figure 1 below). This of course is already happening informally since students choose to do a lot of studying online at home as well as on-campus.

Figure 1

Deliberate design

The difference is I see instructors deliberately designing courses to exploit the comparative benefits of both online and face-to-face teaching, and in particular, the asynchronous benefits of online learning.

Research shows that in blended learning, student performance improves over both face-to-face and fully online learning (Means et. al., 2009). The reason given is students spend more time on task (i.e. work harder) in blended learning courses.

Thus, I am optimistic we will see a considerable change in modes of delivery that will benefit both students and instructors as a result of COVID-19.

For Lesson 2, click here: Support for instructors is essential for quality online learning

References

Johnson, N. (2019) Tracking Online Education in Canadian Universities and Colleges Halifax NS: Canadian Digital Learning Research Association

Means, B. et al. (2009) Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies Washington, DC: US Department of Education

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.