OCUFA (2020) OCUFA 2020 Study: COVID-19 and the Impact on University Life and Education Toronto ON, November

HESA/The Strategic Counsel (2021) The Future of Learning: A Report from the Front Line Toronto ON: January 24

I am analysing here the results of two important surveys on Canadian university student responses to the measures put in place by Canadian universities in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. I have put these two together because, although their results are similar, their interpretation of the results are quite different. I do not intend to be a referee but more an engaged and somewhat partisan spectator.

Who did the studies?

OCUFA (The Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations) is the voice of 17,000 university faculty and academic librarians across Ontario. In November 2020 it published a survey of faculty and students from the 21 universities in Ontario. This report is publicly available.

HESA (Higher Education Strategy Associates) is a private consultancy company that provides strategic insight and guidance to governments, post-secondary institutions, and agencies through … expertise in policy analysis, monitoring and evaluation, and strategic consulting services. The Strategic Counsel is another, more general, private consultancy company that among other things offer[s] tailored research services for post-secondary organizations for brand development and positing, to manage issues, develop and test student recruitment communications, enhance alumni relations and more.

HESA/The Strategy Counsel conducted a survey of university students in 23 universities across Canada, of which eight were in Ontario, in December 2020. Their report is behind a $5,000 a copy paywall. (A client has shown me a copy of the full report. I reported a summary of the results earlier). I will use HESA as shorthand for HESA/The Strategy Counsel.

Objectives

OCUFA

Not directly stated in the report, but the way the report is written, and the press release that accompanied the report, suggest the main aim was to assess the decline in academic quality caused by the move to online learning in response to the pandemic.

HESA

The overall purpose of the research is understand the experience of university students of online learning in the following areas:

- Overall experience of online learning;

- Satisfaction with specific aspects of online learning;

- Workload issues;

- Experience with different learning formats;

- Assessment of the university’s technology platform;

- Like/dislikes of online learning;

- Assessment of options for improving the online experience; and

- Experience with work integrated learning.

Thus there is a degree of congruence in the objectives of the two studies.

Methodology

The full reports of both studies are presented in slide decks, with the methodology section as bullet points at the end.

OCUFA

OCUFA had responses from 502 university students and 2,208 university faculty and academic librarians in Ontario. OCUFA stated that data are considered representative of the current population of university students and faculty in Ontario. There are approximately 17,000 faculty and administrators in OCUFA, so the sample of faculty is about 13%, which is a reasonable sample.

However, there are just under 300,000 university students in Ontario, so this is a survey of less than 0.2% of students. In no way can it be considered a representative sample of students.

HESA

HESA had responses from 1,392 university students, of which just over 300 were graduate students, from 23, mainly larger, universities from across Canada. Eight of the universities were in Ontario and six in Québec. There was one university (Dalhousie) from the maritime provinces. Just over 20% were francophone students and six per cent were international students. Female students were over-represented (70% compared with 57% in the total university student population).

There are approximately 1.3 million students in Canadian universities, so the HESA sample is about 0.1% of all students. No details are given about how the sample was drawn or located. However, it appeared that in this study, students were interviewed, although the interview was short (11 minutes).

Comment

In essence, given the very small sample size of students in both studies, and the lack of information on how students in the samples were drawn or identified, great care is needed in interpreting the student data, so this should be borne in mind when discussing students’ responses to the pandemic. In particular, I see the OCUFA study as one mainly of instructors and faculty, given the disproportionate representation of faculty to students in the sample.

However, if the two studies are taken in conjunction with similar, independent studies (see here for a list), they contribute to a more general picture of student responses.

Main results

I am being a little selective in reporting the findings, mainly looking for those areas where there are similarities in the questions between the two studies.

I am also going to be careful here, giving the actual results where possible, rather than the spin put on the results. However, it should be noted that neither OCUFA not HESA makes a distinction between online learning and emergency remote learning throughout their reports.

1. Negative impact

OCUFA

OCUFA asked the following question of students:

Thinking about all of the adjustments that your university has made to protect faculty, staff and students and staff against the risk of COVID-19, overall how do you think this has impacted the quality of your teaching?

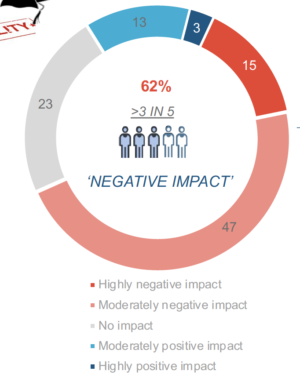

Just under two thirds (62%) reported either a ‘highly negative impact’ (15%) or ‘a moderately negative impact’ (47%). On the other hand, 16% reported a highly positive impact (3%) or a moderately positive impact (13%). Nearly a quarter (23%) reported no impact.

The main reason given for the negative impact was isolation/lack of communication with professors.

On another question though 77% of students reported a negative impact on quality of course instruction/teaching. Faculty were equally negative, with 76% either reporting a highly negative impact (17%) or a moderately negative impact (59%).

HESA

HESA asked a slightly different question:

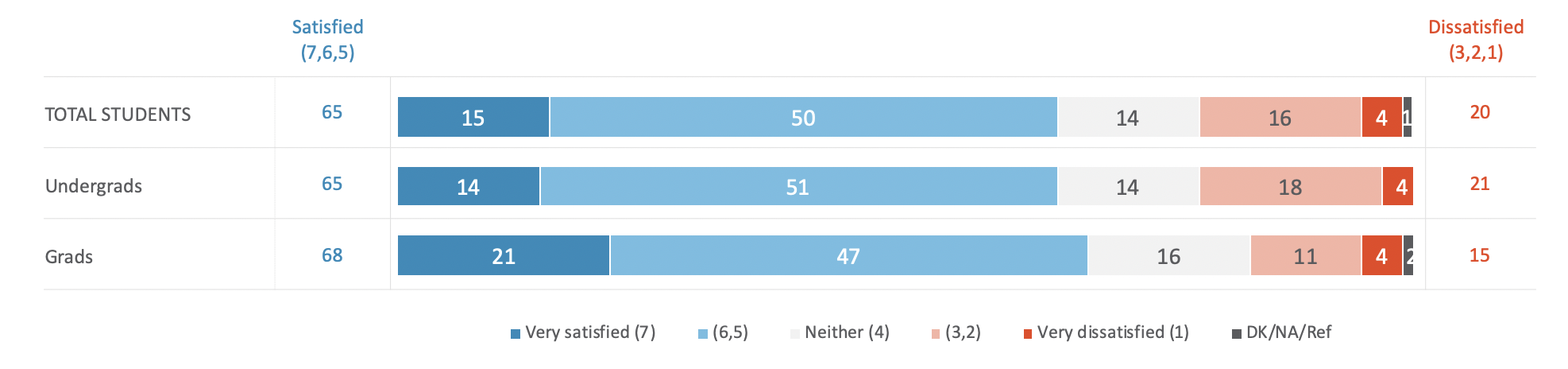

Overall, how satisfied are you with your experience at [your university] so far this term?

Here the results were ostensibly the opposite of OCUFA’s. (HESA used a seven point ‘satisfaction scale’). 65% were satisfied and only 20% were dissatisfied.

However, HESA commented that ‘this is lower than levels generally seen in surveys of students.’ One interpretation of the difference is that both studies revealed less satisfaction than with normal, but in the HESA question students were taking account of the difficulties during a pandemic. Also this HESA question did not specifically ask about the quality of teaching. This was addressed in other questions.

72% reported that they missed being on campus and 70% wanted a return to campus as before Covid-19. The greatest cause for dissatisfaction was the loss of social life on campus.

Nevertheless 40% reported liking taking online classes and 44% said that the quality of the online classes were better than expected. Perhaps most significantly, 61% reported that ‘There are no real attractive options other than to continue university, even if mostly online.‘

2. Social factors

Both surveys brought out the importance to students of the social aspects of a campus-based education, and the loss of this is a major reason for lower student satisfaction.

OCUFA

In the OCUFA report, 85% of students reported a negative impact on my ability to participate in extracurricular activities, 77% reported that it was more difficult to access important learning resources (student tutorials, informal study groups, libraries)

HESA

HESA results also commented that online learning appears to be depriving many students of aspects of what they feel is a complete university experience. University, for them, is a complex experience consisting of more than just academics.

3. Mental health/stress/cost

Mental health, stress and workload were also issues reported by students in both surveys.

OCUFA

55% of students expressed concern regarding mental health due to changes and challenges arising from COVID and just over half reported financial difficulties due to inability to work part-time or cover their costs of education. 83% of faculty also complained about the increased workload.

In particular, students complained about the high cost of tuition when they were not getting the full campus experience.

HESA

62% of students reported I feel more stressed than normal as a result of the shift to online learning and 50% were struggling to keep up with the workload.

4. The future of online learning

OCUFA did not really ask about this. Most of its questions required students to agree or disagree with largely negative statements. It did ask about what should be done to improve the educational experience post pandemic, but these were open-ended questions, and not surprisingly the most popular suggestion was to reduce costs or more financial help (15%) but then almost as many suggested closing the campus or going online (13%).

HESA though asked more neutral questions about the future, and where online learning fits. 62% of students were resigned to the fact that there are no real attractive options other than to continue university, even if mostly online.

94% of students reported at least something they liked about online learning and just over half liked the ability to review materials and the flexibility it provided.

Two-thirds are willing to continue online until in person courses resume, but 18% do not want any courses online. Over half would like either online only (15%) or a combination of face-to-face and online (42%) courses in the future.

Almost a third (30%) said they would prefer online learning to the large introductory lecture courses. In particular, 75% think more engaging lecture styles would improve their online learning experience, and 71% wanted better use of visuals.

Conclusions/implications drawn by the authors

This is where the differences become more obvious.

OCUFA

It seems clear that both from the design of their study and the conclusions they drew from it that OCUFA’s main goal was to denigrate the educational value of online learning.

You will have noticed that many of the results (in both studies) were about the general effects of closing campuses. This is fair enough. But OCUFA seems to put the blame not on campus closures but on the quality of the online learning that resulted from the closures. For instance, this is how OCUFA’s web site commented on the study:

The results of the poll also make it very clear that, even once the pandemic has ended, online education will not see the enthusiastic adoption that many have claimed. On the whole, neither students nor faculty view online learning as a desirable approach to a university education.

The report itself states:

The main area of dissatisfaction focus on the lack of interaction and engagement resulting from the migration to online learning/delivery of course material.

The OCUFA report states that students are demanding changes such as reducing tuition fees, providing more course options as long as campus access is reduced, adjusting workload and providing student support as well as supplying PPE.

Reading the OCUFA report and comments reminded me of the days of David Noble and his assault on ‘digital diploma mills‘ back in the 2000s.

HESA

HESA argues that the future is more complex, divisive and polarizing after the pandemic. HESA also agrees that online learning is not the future most students want. However, most students accept that online learning is here to stay in some form. Indeed about a third of undergraduates have a very positive attitude toward online learning.

Consequently, in his blog post on the survey, Alex Usher wrote:

nationally, we are talking about 200,000 to 400,000 students who might be open to making remote education a permanent part of their education. Even if you take the more conservative number (always the right choice in higher education), that’s a simply massive potential client base for a university that wants to go big into remote instruction.

(According to data from the CDLRA, pre-Covid there were already about 1.36 million online credit course registrations in 2016/17).

Both these reports cover more areas, such as responses to health and safety measures, and again I recommend that you go to the original reports (if you can afford it) for a more nuanced interpretation.

My comments

These studies are important because the student response to emergency remote learning is of course important in itself. It is also a difficult area of study because of the size and diversity of the Canadian student body. We really need more expansive (and less expensive) studies of students’ responses with larger/more representative samples and more emphasis on learning outcomes, but in the meantime the HESA study asked some good questions and provided some data that I haven’t seen in other studies. The OCUFA study though was frankly disappointing.

OCUFA got it wrong. It isn’t online learning that caused students’ dissatisfaction, but Covid-19, which forced institutions to pivot away from on-campus teaching.

What mainly happened was that face-to-face teaching – mainly lectures and end of semester witten exams – was shifted online (emergency remote learning). This is not how online teaching is supposed to be done; it needs re-design, and it needs to be focused on students who most need it as an option, not a replacement for all full-time, campus-based teaching.

However, this was a health emergency. In fact, instructors in particular did a tremendous job in shifting all their teaching off-campus within a two-week period. Was it pretty? No. Was it good quality online teaching? No. But it saved the semester for students. The alternative was not an equally satisfactory university experience delivered in some other way but no semester and an interrupted or lost academic year.

Yes, universities and colleges should have been better prepared for moving online in a more professional way, especially by the Fall semester. Before Covid-19 struck, most universities and colleges in Canada offered some online learning in an effective, professional way. About two-thirds had a plan for e-learning or were implementing one. Thus, most Canadian post-secondary institutions knew how to do online learning well.

The problem was scale. Until Covid-19, less than 10% of courses were online, but now ALL courses had to be online. This requires a massive re-design of courses and training of instructors. Many institutions have done all they could from March to now. Covid-19 has moved forward these plans by several years, but there is still a lot of catching up to do.

It should be noted that it was not just Ontario but the whole of the world that had to pivot to emergency remote learning. Especially in the USA, students returned to campus too soon in the fall and, despite special health precautions, many got sick, and more importantly infected others in their family. Canada probably managed the move to emergency remote learning as well as any other country, and much better than most. Great credit is due to students, instructors and administrators for this.

And yes, thank you, HESA, for letting us know that there is a sub-market for online learning and that it suits some students (older, working introvert) more than others, and this market is going to grow. But we’ve always known this.

The value of these studies is that they reinforce something that I think everybody already knows. Covid-19 is horrible not only in itself, but in all the disruption it causes. Yes, it’s been a terrible year for university and college students and it is likely to go on, I’m afraid, for another year. Our students have suffered particularly while being the least vulnerable to the virus.

Both these studies reflect what students have lost, and it is very sad. But we have to do the best we can in the circumstances, and criticising emergency remote learning for not being perfect is not helpful. Conflating emergency remote learning with quality online learning is particularly galling, OCUFA. But it won’t make online learning go away. We need more good quality online learning and that means instructors – and especially organisations such as OCUFA – will have to change. In the meantime, the message from these studies is: Covid-19 sucks.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Thanx for this. I wonder at Usher’s conclusion that there is a ‘massive potential client base for a university that wants to go big into remote instruction.’ In Canada Athabasca University has gone ‘big into remote instruction’ yet I am not aware that it is being swamped by a ‘massive potential client base’.

Rather, I observe that students are studying fully online and hybrid at universities which have added hybrid and fully online education to their on campus education.

You’re right. Some institutions (e.g. Université Laval, BCIT) have a high percentage of online course enrolments already. Université Laval has as many online course enrolments (80,000+) as Athabasca; 42% of all BCIT’s enrolments are online. Algonquin, Fanshawe and Centennial colleges in Ontario also have a high proportion of online enrolments.

I expect that growth in (fully) online enrolments will continue at a rate of about 10-15% per annum. With enrolments from high school going down in many provinces, and lifelong learning increasing, I expect the proportion online to increase, but the main growth is likely to be in Continuing Education, with online certificates, diplomas and microcredentials for adult learners looking for jobs or upgrading.

The big growth though should be in blended/hybrid learning, but I worry about HE institutions’ capacity to revert to solely face-to-face teaching once Covid-19 is over.