This is the fourth in my series reviewing developments in online learning in 2018. The first three were:

Five factors driving the development of online learning

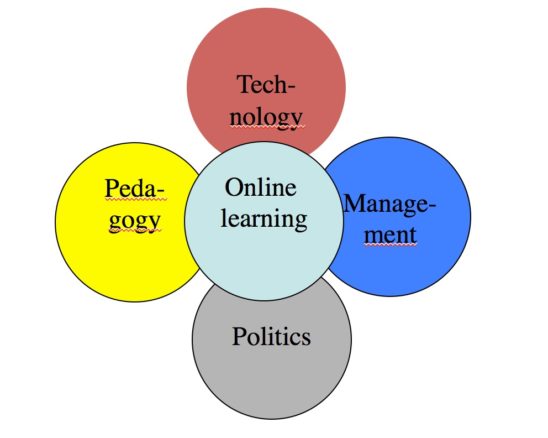

There are at least five factors that affect the growth and the success of online learning, best illustrated through the following Venn diagram:

Figure 1: Five factors influencing the growth of online learning

The five key ‘drivers’ of the development of online learning are:

- student demand driven by personal circumstances such as family, part-time or full-time work, career development;

- pedagogy or educational theory and ideas, such as independent learning, flexible learning, open pedagogy;

- technology, such as the development of the Internet, the web, learning management systems, etc.

- external politics (internal politics will come under management): it is clear from both the 2017 and 2018 national surveys that government policies through earmarked funding for online learning – or negative policies such as cutting student aid for part-time students, aka the U.K. – can have a major impact on the growth of online learning;

- management: this is the effectiveness of institutional strategies and planning that are developed to support the growth (and quality) of online learning.

Far too little attention has been paid to the inhibiting or dynamic effects of institutional management on the growth of online learning, but I believe this to be a critical factor, and I had considerable evidence of this from my work during 2018.

Well done, Canada

First, let’s look at the positive side. The 2018 national survey of online learning found that almost all universities in Canada, and almost all colleges outside Québec, are now offering at least some online courses. Those that are not are mainly very small institutions (under 1,000 students) and/or are semi-private colleges or Cégeps in Québec.

Now let’s just stop and think about that in the big picture of university and college education. In 20 years or so, Canadian universities and colleges have gone from no online learning to almost every institution outside Québec offering at least some online learning as part of degrees or diplomas. In 2017 there were over 1.3 million student enrolments in fully online courses for credit. In terms of FTEs, this is equivalent to four universities of 27,500 students plus another four colleges of 12,000 students and a Cégep of 3,000 students. Given an 800 year history of universities, this is a massive change in a very short time, because online learning in general reflects a significant shift from the traditional classroom experience.

But how much of this is due to institutional leadership, and how much has been due to heroic efforts by individual faculty and instructors, friendly government policies, and above all pressure from students?

Weak leadership: two examples

I am going to argue that in general, a majority of post-secondary educational institutions suffer from weak leadership in the area of online and digital learning. I realise this is both controversial and not altogether new as it has been a recurring problem since the onset of online learning. However, in 2018 I heard of at least two classic cases of weak leadership in dealing with the challenge of change resulting from the introduction of new technologies, and online learning in particular.

In one instance, because of demands from students who were mainly working, but also because the department saw a market opening, an academic department decides to launch a professional, one-year ‘blended learning’ master’s program, at a fee of $50,000 per student. The strategy was to reduce campus-based lecture classes from three to two a week, with the third lecture being delivered synchronously over the Internet. Students would be required to attend the live transmission ‘because you can’t have a proper discussion if students aren’t all present at the same time.’ There was no project management, no change of course design, no course director, and three months before the course was due to be launched, no confirmed instructors. Worst of all, the department was not listening to the advice of the Centre for Teaching and Learning.

In another case, under pressure from a couple of deans, the acting provost of a large university summons all the deans to a meeting to discuss ‘what we should be doing about e-learning.’ An external expert is invited to address the meeting for about 20 minutes. This is followed by a largely unstructured discussion where it is clear that about a third of the deans are anxious to move ahead rapidly with blended and fully online courses for credit, about half are open to moving but need more resources and technical help before making any commitments, and one or two are sullenly quiet, suggesting opposition. To solve the problem of the need for more resources, the CIO suggests that the instructional designers and tech support people located in Continuing Studies, which is supporting successful non-credit online programs, should be moved to his division to support on-campus blended programs. The meeting ends without any decisions made. Twelve months later, the situation remains the same, under a new Provost.

Two swallows a summer do not make. In fact, both these institutions have a generally good academic reputation, and indeed offer some really good online courses. However, I don’t think these two cases were exceptional but reflect a systemic problem, especially in universities, but also in colleges as well, in dealing with change and innovation.

The task of senior management

University and college academic leaders have essentially two interlinked but different tasks in bringing about innovation and change:

- direction and

- agency.

For instance, what is the vision and direction for teaching and learning? What are the institutional priorities? In particular, where does online learning and digital technology ‘fit’ within the broader teaching goals of the university? For instance, can blended or hybrid learning be used as a means of developing some of the core skills required by students?

In fact, most Canadian post-secondary institutional administrations do have a reasonably clear direction for online and blended learning: more. In the 2018 survey more than two thirds think that online learning is a very or extremely important part of their strategic or academic plan. Almost all institutions (95%) recognise it is important to have a plan or strategy for online learning, although only a third actually do have a plan or strategy. Most believe that online learning enrolments will increase in the future and most believe that online and blended learning is of the same or higher quality as face-to-face teaching. So general direction is not the problem.

But once that direction is set, how can it best be implemented? I deliberately use the term ‘agency’ rather than implementation, because management or ‘the administration’ is unlikely to do the actual implementation. In universities and colleges, this will inevitably be the job of the instructors. So it then becomes the task of persuading or helping instructors to move in the desired directions that are set. And this is where the systemic barriers kick in.

Systemic barriers

It is the agency part that is lacking: identifying and providing the resources needed to support online learning, and in particular putting in place the necessary faculty development/training to ensure that online and blended learning gets done well. This is not happening, or rather it is not happening fast enough, in many institutions, because of the following systemic barriers:

Academic hierarchies and academic freedom

Let’s start with academic freedom. In essence, faculty have the right to teach well online, to teach badly online, or not to teach online at all. In my first case, there is little the senior administration can do to stop the disaster that it is to come. Without a plan or strategy and a set of criteria for quality teaching signed off by all the departments, all the senior administration can do is to try and persuade the department to do things differently – if it is even aware that there is a problem.

And this leads to my second point. There is an apartheid and hierarchy in universities. There are tenured faculty, contract faculty, and staff. Most learning technology support people are staff, and hence do not have to be listened to.

This is then augmented by the fact that those making decisions about learning technologies and course design, the AVPs Teaching and Learning or Provosts, the Deans and even heads of Department are themselves academics and generally have little or no expertise in either pedagogy or learning technologies (although often they are successful classroom teachers).

In successful institutions, this does not matter if such administrators listen to and support the advice from specialist staff. But many distrust or do not value such advice, because they do not have the knowledge base from which to make such judgements. If you don’t know, go by instinct and past experience, if the advice you receive is inconvenient or difficult to implement.

Management turnover

To implement a successful institutional strategy of any kind, you need time, especially in large institutions. For instance, it will probably take a minimum of five to ten years to ensure quality blended and online learning throughout most of an institution, if there has been little to start with.

However, one thing I noticed when drawing up the roster of institutions for the national survey is that approximately one third of all Provosts in universities and VP Education in colleges changed between 2017 and 2018. In Canadian higher education, the churn rate of senior administrators is very high. Few serve a full five-year term. This makes coherent strategy implementation very difficult.

One problem with strategy is when it becomes personal, i.e. driven by a particular individual, such as a charismatic Provost. Without a broad-based institutional strategy, once that individual leaves, the strategy stops. Sometimes the process of hiring a senior administrator can take longer than the term they actually serve, during which time there is a policy vacuum. That clearly happened in my second case.

The only way to deal with management turnover is to develop a strategy that is accepted by the whole institution – which in turn takes time. As a result, too many faculty just shrug their shoulders when the latest strategy or plan is extolled: wait long enough and it will go away.

No need to be qualified to teach

I have written many times about the need now for all faculty and instructors to have basic pedagogical knowledge and skills if they are to teach effectively in a digital environment, but this is not a requirement for teaching in a Canadian university and is unlikely ever to be one while research is the predominant criterion for career advancement.

Nevertheless we could be doing much more to provide faculty with course design templates for online and blended teaching, online research-based resources (such as how most effectively to use video), and educational consultants that they can work with, especially the first time they tackle a blended or online course.

However this means building a support structure and staffing it adequately. Most institutions are moving towards this, but not quickly or extensively enough – faculty now are moving more quickly to at least partly online with their teaching than the development of support. Without such support though quality will suffer.

Online learning management in 2018

In essence I don’t see any easy solutions. I think the best that can be said is this:

- there are a few institutions that have shown outstanding leadership in trying to move the whole institution towards more flexible learning opportunities and the planned growth of online learning. I would say that the number of institutions in Canada that fit this profile can be counted on the fingers of your hands, and I’m willing to name some: UBC, Queen’s, Waterloo, Ottawa, Algonquin, Memorial. There are others, but not many, and even some of those in this category have struggled to implement their strategies

- there is a larger bunch – maybe 30-50% – that have strengthened Centres for Teaching and Learning and brought in educational technology specialists, but have left it to individual faculty or academic departments to grow into online learning. This has been largely successful in terms of getting online learning established, but it is still very much a hit or miss approach. For instance what is the rationale for the size and type of support staff? Nevertheless I’m open to considering that this approach may be at least as successful as the command-and-control approach from the Provost’s Office in getting online learning established and of reasonable quality

- then there’s the rest which I am guessing is at least 50% of our institutions in Canada, where nearly everything has been left to the faculty/instructors and what little there is of existing technical and pedagogical support services. For instance there may be a small and overwhelmed Teaching and Learning Centre – I know one university of over 40,000 students that has only one support person serving the whole credit-based part of the university in online learning – but there is no clear rationale for the size of any support service and a very wide mandate that probably includes all teaching and learning, including online.

What can be done to help this large chunk of institutions that have no effective strategy or plan for implementation?

The eCampuses could take leadership here, and provide workshops and courses for senior administrators, bringing in speakers from institutions that have been successful in implementing strategies for digital, flexible or online learning. I would argue that this is a much higher priority than driving OER initiatives, for instance.

Government funding could also be used to support province-wide online courses for graduates wanting to teach in universities and colleges, and using access to funding to lean on universities and colleges to make this a requirement of hiring new faculty.

These are just two small strategies. As I said, there are no easy solutions, but the first step is to recognise that we have a problem, Houston. We need a better management system in our HE institutions if we are to move from a 19th century system of higher education into the 21st century, and that will mean removing some of the systemic barriers that inhibit change.

Next up

The last post in this series will look at developments in pedagogy and online teaching during 2018, and then – hooray – it will be Christmas and time for a short break.

Over to you

- Have I been too harsh on senior administrators?

- Does what I am saying match your experience?

- Does your institution have a successful implementation strategy for supporting online/digital learning? Can you share it?

- Any other horror stories?

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Tony’s unbridled enthusiasm and commitment to online learning has to be admired. He has done so much for online learning, especially in Canada, and represents a true public champion and just what a profound and capable public scholar should be: calling it as he sees it.

His most recent post on Weak Leadership, in which he offers a critique of the leadership of public post-secondary education leadership and its lack of strategic focus, will attract a lot of attention and response. He suggests that the undoubted achievements related to online learning in Canada are more accidental than strategic, more about “bottom up” risk-taking than focused, directed and deliberate public policy or institutional strategy, especially in universities.

In his analysis Tony underestimates the role of financial impediments to change – the funding model for post-secondary education in Canada, which has seen the systematic reduction of public per capita funding and the growth of private funding through student fees; the role of new public management (NPM) and the inhibiting impact the adoption of competition and market ideologies by all Canadian governments on the education system as a whole; the role of corporations and their vested interests in shaping public policy; and the role of the academy in enabling innovation on a limited scale, especially given the inhibiting role of quality assurance agencies in Canada. In short: the developments in higher education are more complicated than Tony’s account would have us believe.

To overcome these challenges Tony is right to say that we need new bold, creative and status-quo challenging leadership. What he fails to recognize is that this is why we have such a high turnover of educational leaders in the system and why so few want these positions – such bold leadership does not secure the support of either Government, governing boards or faculty. The turnover of Provosts and Presidents is increasing and the financial position of many colleges and universities is becoming more perilous, with many now facing deficits. The coming recession (widely forecast by economists of many different stripes) will make these positions more difficult, as costs rise and enrollment falls in line with forecast demographic shifts. We are likely to see mergers and acquisitions, budget cuts and retrenchment rather than innovation. Who would want to be the risk-taking leader under these conditions?

For Tony’s vision of more public institutions doing very different things, we may need to see collapse and rebirth before we see true leadership and innovation. The recent near-collapse of Athabasca University and its emerging rebirth may prove an example for others to follow.

What is clear, at least to me, is that things will get much worse before they get better. Online learning will continue to emerge as part of the different future, as will micro-credentials, assessment-based credentials, anytime admission and new models of program delivery.

I hope I am wrong. But I do have a T-shirt which says “I May Be Wrong, But I Doubt It!”.

Many thanks for your (as always) thoughtful comments, Stephen. I agree with you that the situation regarding academic leadership is far more complex than I could cover in one blog post. For readers who would like the bigger picture, I would recommend Stephen’s own book, ‘Renaissance leadership‘ or Ross Paul’s ‘Leadership Under Fire: The Challenging Role of the Canadian University President.’

However, my underlying criticism regarding leadership in online learning is still valid. In terms of the bigger picture, university and college leadership is still a little bit like gentleman athletes in the 19th century. There are very good fellows (or increasingly dames) and do their best under the circumstances and follow the rules scrupulously but they are not professional managers or leaders. They do not see leadership as a skill developed over a career that focuses on leadership but a temporary duty to be carried out to the best of their abilities, which are primarily in areas such as research and sometimes teaching – but not leadership. (I am making the distinction here between ambition and the consistent development of leadership skills.)

As well as a lack of knowledge at a deep level of best leadership practices, current academic leaders often also lack an understanding of the key issues in learning technologies.

Stephen and Maxim are right in that academic leadership is a truly thankless task and will remain so unless the whole system changes. My point here is not to blame the individual senior administrators who have to carry out such thankless tasks, but to try to understand what could be done at a system level to enable a better, more effective leadership environment that is still true to the core values of higher education.

For instance, how about better career projectories for learning technology staff? Wouldn’t it be nice to see someone from this area become an AVP Teaching and Learning for example? Or what about a ten year contract for a Provost appointed to develop and sustain a clearly articulated strategy for the future of teaching and learning?

Lastly, I am not pessimistic about the future of online learning in Canada. Criticism is optimistic because it suggests that things can be better.

As I said, I don’t claim to have the answers, but I do hope that we will be frank and acknowledge that there is a systemic issue here, and that we try to have a grown-up conversation about how to solve this problem without tearing down the whole system of public higher education.

TEN REASONS TO BE OPTIMISTIC ABOUT ONLINE LEARNING IN CANADA IN 2019

Both Tony and Stephen have made and continuing to me significant contributions to Canada’s online learning space, which is why both were granted (at different times) Honorary doctoral degrees by Athabasca University which, under its new leadership, is on path to long-term success. But now both seem remarkably pessimistic. Tony is concerned with the lack of effective, focused, strategic bold leadership. Stephen seems to be focusing on systems paralysis in the face of coming fiscal and demographic challenges. Both make me feel proud to be optimistic.

First, online learning, as Tony rightly observes, is growing in leaps and bounds. My Contact North I Contact Nord see significant and substantial growth not just in registrations, but acceptance of online learning

Second, we do have institutions in Canada strategically embracing online and blended learning, and Ontario is a leader. In this province we have over 20,000 online courses, close to 1,000 certificate, diploma and degree programs fully online and over 7000 literacy and basic skills and training courses online. A number of Ontario’s 24 public colleges and 22 public universities see online as strategically central to their work.

Third, when we look at the shift in teaching and learning – from chalk and talk to engaged learning – we see it everywhere and there is genuine, dynamic and focused conversations about engaging students in active ways in their learning.

Fourth, colleges and universities are embracing gamification, augmented and virtual reality and simulation as part of their designs for online and blended learning. They are doing so to increase relevance, engagement and the focus on skills.

Fifth, as more and more students engage in work-based and project-based learning, more of them are making use of collaborative and video-based dialogue systems and peer learning networks to support their practical learning.

Sixth, the boundaries between continuing education and credit-based learning is becoming increasingly blurred, especially with the emergence of micro-credentials and the growing “stackability” of these micro-credentials.

Seventh, Stephen is rightly concerned about the way in which the funding of learning occurs – but the growth of online learning – from virtually nothing in 1998 to it being a substantial component of the system and the learner experience – has occurred while funding has dropped from 65% of university / college funding to nearer 45% across Canada: tightening economics is a stimulus for change, not an inhibitor.

Eighth, online learning is finding new avenues. E-Apprenticeship is a growing focus in Ontario as is the more widespread use of open education resources. As the online learning environment shifts and changes – and it will continue to do so, especially with the emergence of AI enabled systems – we can expect more utilization of technology not only to enable access, but to enhance learning.

Ninth, I am not sure what Tony finds disappointing in the system as it emerging. What I say is vibrant innovation, highly focused and committed leadership and dedicated colleagues working every day to imagine new designs for learning. I am an optimist. We have lots of evidence (look at the 185 + Pockets of Innovation in Online Learning from Ontario, Cross Canada and Around the World at https://teachonline.ca/pockets-innovation/overview) which supports my optimism..

Finally, and it reflects the observation Stephen makes, management and leadership positions are tough, demanding and challenging. They are not for everyone and few who take them are prepared for the reality of the work they encounter. Yet, look at our universities and colleges – look at their constant ability to change, surprise and develop. You have to admire their resilience.

It’s Christmas and time for good cheer.

Let’s be optimistic for 2019 and the future of online learning. I am.

Seasons greetings!