The issue

I came to this conclusion in the middle of the night by worrying at the distinction between synchronous and asynchronous learning. (Yeah, I know, Tony, get a life). This distinction is getting a lot of attention at the moment due to emergency remote learning.

Now let me say immediately that in teaching, it is what is done in practice, not what may be superior in theory, that matters, but I make this deliberately provocative statement, because I am hoping it will shed light on some confusion about face-to-face teaching, online learning, and synchronous and asynchronous teaching.

The proposition

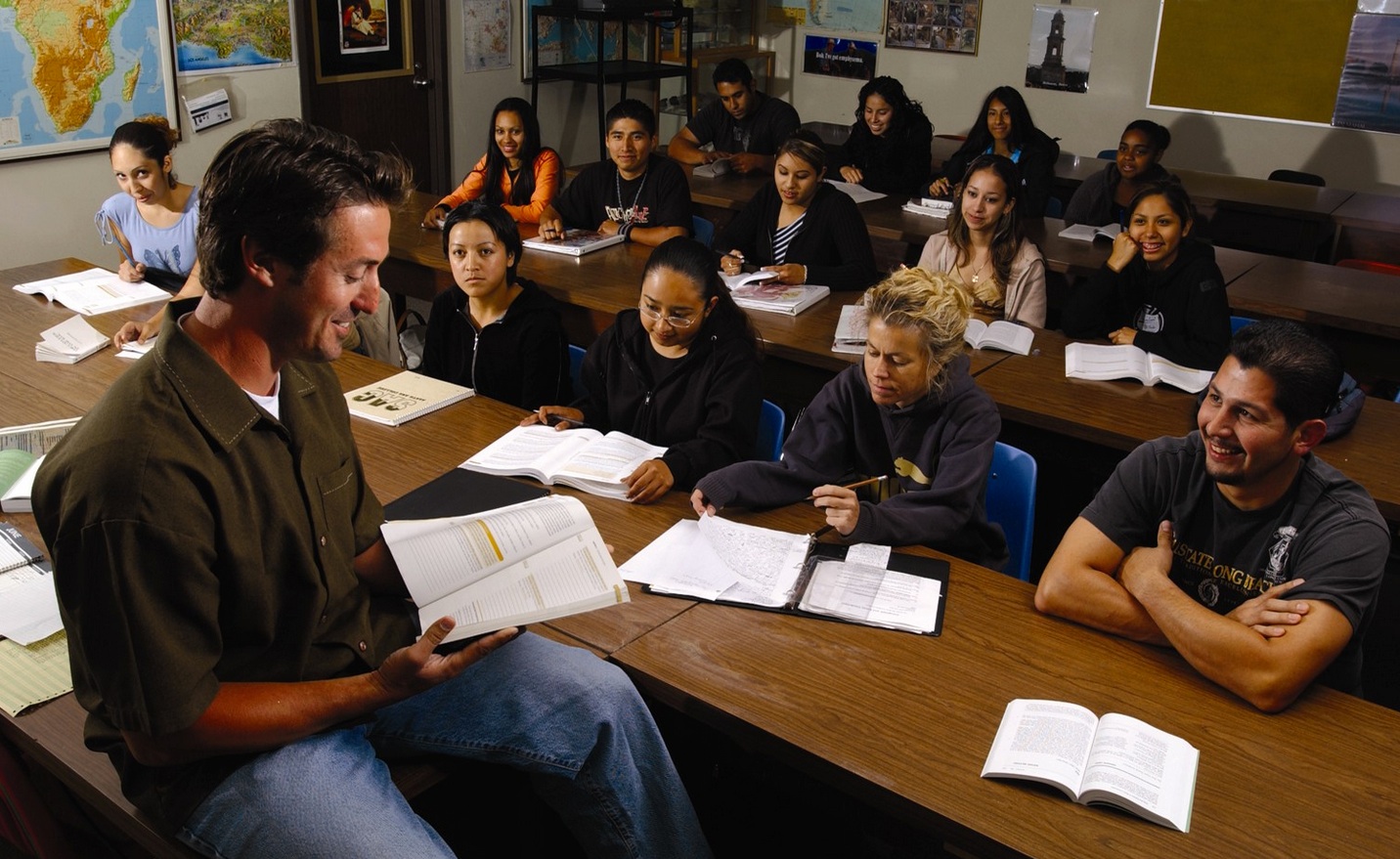

Face-to-face teaching by definition is synchronous AND, more importantly, place-based. Everyone has to be together at the same time and place. Online learning though can be synchronous (e.g. through a Zoom lecture), OR asynchronous (through, for instance a learning management system).

We know that there are certain educational advantages of asynchronous learning (opportunity for more time on task, ability to repeat the experience through recording and playback, and availability to study any time and anywhere).

Thus there are benefits of online learning that do not exist in face-to-face teaching, whereas there are no benefits in face-to-face teaching that could not exist in online teaching.

Ah, I hear you say, but that ignores the unique benefits of face-to-face teaching, the ‘affordances’ of people being together at the same time and place, such as the heightened emotional context (think rock concerts and sporting events, or, in the case of teaching, an inspired lecture and heated discussion that follows.)

Certainly, in practice, what makes teaching effective in either mode are the conditions within that mode. In other words, you can do online learning well or badly. The same applies to face-to-face teaching. Badly designed online learning (hello, emergency remote learning) will be worse than a good face-to-face lecture. However, you cannot make face-to-face teaching itself by definition asynchronous, so all those potential benefits of asynchronous learning are lost.

Also, it should be noted that you do not have to be online to learn asynchronously. Books are an asynchronous medium. Students learned asynchronously long before computers were invented; they did homework.

Finally, synchronous/asynchronous is not the only dimension that matters. There is another, independent dimension, broadcast/communicative, that we should also be considering (see Teaching in a Distance, Chapter 7.5). A major structural distinction is between ‘broadcast’ media that are primarily one-to-many and one-way, and those media that are primarily many-to-many or ‘communicative’, allowing for two-way or multiple communication connections. Communicative media include those that give equal ‘power’ of communication between multiple end users.

However, there is no obvious advantage for face-to-face teaching in this dimension, either. Both these elements can exist in face-to-face and online learning. However, we need to pay as much attention to these elements of teaching as to the synchronous/asynchronous dimension. Are we focusing on broadcasting from one to many; or on everyone in the group communicating with each other? If so, which medium is the most appropriate, and under what conditions?

Why does it matter?

The logically superior benefits of online learning matter because it forces us to examine some common misconceptions.

First: synchronous learning is not unique or synonymous to face-to-face teaching; synchronous learning can also be done online.

Second: we need to focus then on the affordances of being in the same place physically and at the same time, to justify the inconvenience and cost, (and the risk with Covid-19 or even the flu or common cold), and the loss of the affordances from learning asynchronously. In particular, what does same-time, same-place group work add to individual study, and when does it have to be face-to-face, given that we can have both synchronous and asynchronous meetings online? Are we maximising ‘the group all together’ experience when we bring students together? What are the benefits of one-on-one, face-to-face interactions between an instructor and a student compared with asynchronous communication? Under what conditions can we justify face-to-face presence?

Third: it is not either/or: we can have face-to-face, group-based learning, and online study that either follows up or prepares for the face-to-face group meeting. Group work can be done effectively online, as well as individual study. But we still come back to asking what determines when group work is best done face-to-face, again taking into account the convenience of online learning?

There are of course probably good answers to all these questions, and these will vary depending on the subject matter and the needs of different students (not to mention the convenience of administrators). But they do need to be asked and answered by each instructor.

What we can take away from this discussion is that it is not online learning that now needs to justify itself, but face-to-face teaching. So go ahead!

Footnote

We can probably learn a lot from watching sports. There is nothing to beat the experience of being in a packed stadium during an important and exciting match. I was at Wembley in 1966 when England beat Germany in extra time to win the World Cup. It was the most exciting experience of my life, even though I didn’t see the actual winning goals because I was at the other end of the ground. (I had to wait to get home to see them on television – they did get shown a lot in 1966).

I was also in Vancouver watching the Stanley Cup final in 1994 in local pubs – again the excitement watching synchronously but not being ‘there’ was still immense. This was synchronous but distant.

Now I watch English soccer here at home in Vancouver through a streaming service (I’m a Tottenham Hotspur fan). Because of the time difference (too old to get up at 5.30 am to watch a match live), I watch the recording, but my sons in England will occasionally phone me to tell me the score before I’ve seen the recording and I’m furious with them – it’s not the same (they do love winding me up).

I don’t want to know the score in advance – it spoils the whole experience. This sometimes means sitting for nearly two hours watching an incredibly boring 0-0 draw. I only do this for Tottenham games though – DAZN does three minute highlights of each game, but again I’d rather not know the score beforehand. But I can get close to the synchronous experience watching a recording – so long as the conditions are right.

The lesson: ‘live’ is not necessarily the same as ‘synchronous’: there is an added emotional element to a live event that we should not underestimate.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Face to Face teaching can be asynchronous.

Thanks, Natalie – but in what way?

The interesting part of my Masters research on the subject of cloud based learning was that some of those training using cloud based tools didnt class themsleves as doing online learning but rather F2F training. Yet 50% or more of the learning was occuring in the cloud, funny that, perception:)

‘Logically’, I completely agree with you. But in practice, I’m still not quite comfortable with this remote regime even with all the possibilities offered by online education.

Sorry to be a pedant, but your final image shows Geoff Hurst’s THIRD goal in the 1966 World Cup final, in the last minute of extra time. ‘They think it’s all over … etc.’

Absolutely right – but I couldn’t find (in a hurry) a photo of the second goal (which I also didn’t see directly – just heard the roar at the other end!) I think that was the one the Germans claimed wasn’t over the line. (It was after all a Russian linesman).

Great article thank you. I do think this article skips over an important factor – that of the richness or immersive qualities of the interaction. In a face to face setting the sensory immersion is obviously much deeper than a zoom connection, by this I mean that the information conveyed between people who are co-located is a much richer form of communication. Maybe this should form a key component for consideration in the process you suggest “we need to focus then on the affordances of being in the same place physically”.

I also can’t but take issue with your example of watching the Stanley Cup final in 1994 where you claim “This was synchronous but distant.” Given much of what you are experiencing in terms of the other people in the room presumably watching the same match as you and interacting in that space I’d suggest that is not a fair example of an experience of a ‘distant’ experience.

Thanks, Alexander – all good points. I agree that the ‘affective’ component of being physically together with other people can be a very important contributor to learning, but it needs to be channelled and deliberately exploited by the instructor. Too often the assumption is just put everyone together and wait for the magic.

What your comment though really made me appreciate is the complexity and richness of teaching and learning. We now have so many different ways to teach: f2f-online; synchronous-asynchronous; individual or group; near or far. The decision of the correct balance depends on so many factors: the needs of the subject matter; student factors such as access or preferred learning style; external factors such as accreditation agencies or school curricula; and of course the interests and preferences of the instructor. This is why I believe that teaching will always remain more of an art than a science.

What your comment though really made me appreciate is the complexity and richness of teaching and learning. We now have so many different ways to teach: f2f-online; synchronous-asynchronous; individual or group; near or far. The decision of the correct balance depends on so many factors: the needs of the subject matter; student factors such as access or preferred learning style; external factors such as accreditation agencies or

BUKTI4D