This is the sixth in a series of posts on online learning in the (k-12) school sector.

The first is: What needs to be done about online learning in the school sector? 1. An introduction.

The second is: Online learning and (k-12) schools: 2. Technology and cost issues

The third is: Online learning and (k-12) schools: 3. Do we need a different curriculum for online learning?

The fourth is: Online learning and (k-12) schools: 4. The role of parents

The fifth is: Online learning and (k-12) schools: 5. Creating an appropriate culture of learning online

I need to do some ‘hem-ing and haw-ing’ before I get into the strengths and limitations, for which I apologise, but it is necessary in order to put my later comments in context.

Key differences between k-12 and post-secondary education

There are at least three key differences.

Older – and wiser?

First, in post-secondary education, students are older and, hopefully as a result, more mature. This is important for online learning, because it does require self-discipline and, probably more importantly, the ability to organise and manage time effectively. In the school sector, this requirement is likely to impact considerably on parents and teachers who will need to help children with this.

Again, it is dangerous to generalise. There will be quite young students in the k-12 system who will manage very well to study relatively independent of the teacher, and I know from experience that there are post-secondary students who struggle with the demands of online learning, even when the courses are well designed and there is strong instructor support.

But in general, without wishing to step into the controversial puddle surrounding Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, I would argue the older the student, the better they can handle online learning, and more importantly, the converse, the younger the child the less suitable it is likely to be.

A bigger challenge

Second, k-12 teachers have basic training in teaching methods/pedagogy, whereas, in general, instructors in post-secondary education are primarily subject experts. As a result, pre-Covid, post-secondary instructors often had the advantage of working with specialist instructional designers and media specialists. Although such specialists exist in some school systems, they are more ‘rationed’ and ‘distant’ from teachers in the school system, and, as Covid-19 showed, such support often did not exist at all in many school jurisdictions, at least as far as individual teachers were concerned.

So I am arguing that in general it is going to be tougher for online learning to succeed in the k-12 system, which means if it is to work, more support for both teachers and learners will be required, and in particular the conditions for success in the context of k-12 education need to be identified and provided. In contrast, it is even more important to identify online learning’s limitations for the k-12 sector. In particular, it is critically important to identify when it should NOT be used, or rather what it should not be used to replace.

On-campus schooling the norm – but identify the exceptions

Third, academic learning is just one of many reasons for a public school system. Schools play important roles in the social development of children, children’s safety and security (particularly when parents are working), equitable access to education, and a host of other important functions for society. For this reason I believe all children benefit from regular, full-time on-campus school attendance. I am completely in favour of as many students as possible being in school during Covid-19, as long as it is safe for them and their teachers. Replacing the ‘on-campus’ aspect of k-12 education should be done only in an emergency, or for very specific reasons.

Nevertheless, online learning can not only adequately replace some aspects of school education in an emergency, but can also have value at any time if used in certain ways and done properly. It is these strengths and limitations that I wish to discuss in this post.

Strengths of online learning

Content transmission

While not as prevalent as in the post-secondary system, a good deal of k-12 teaching is about the transmission of information. The learner is required to understand, remember and manage/organise and sometimes even to think critically about the transmitted content. This can be done just as well and in some cases better online (because if recorded the content is permanent and accessible at any time). In this case, little redesign is necessary from face-to-face to online delivery, although if delivered synchronously, the content may need to be delivered in smaller chunks online.

Foundation skills development

This involves reading, writing and foundational math (arithmetic, calculations, geometry). There is a large amount of free, easily accessible material online in these areas. In addition, teachers can set specific tasks that require the practice and development of such skills. Students can spend time online practising such skills, thus releasing teachers for feedback and support for those who are struggling.

Home-based project work

Depending on the age of the child, students can be set home-based project work. The instructions may be delivered online, but much of the work can be done off-screen, giving children a break from screen time. However, they can use mobile phones, iPads or e-portfolios to record and report on their projects, and feedback or assessment can be provided online by the teacher. Such project work can also reinforce foundation skills development.

Online collaborative learning

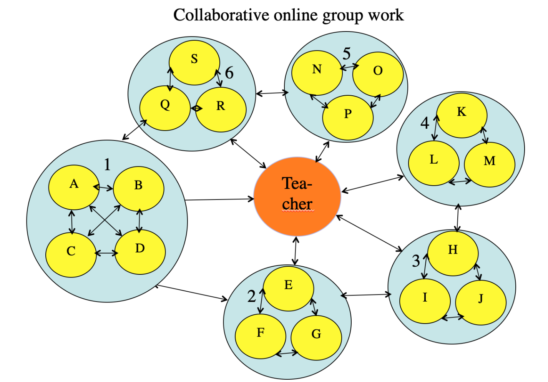

This takes some effort on the teacher’s part. The teacher can use a video-conferencing platform such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams to set up the task, the students can work asynchronously on their individual tasks, then, using the discussion forum in a learning management system (see Figure 1 below), come together in small groups to discuss and finalise the group topic. Zoom could be used for each group to present its final work to the other groups. Online collaborative learning is of itself an increasingly important skill to develop in a digital age.

Knowledge management

This is another increasingly important skill in a digital age: knowing where to find information, how to assess its value/validity, how to apply it to a particular task, and how to organise and communicate it, as well as students learning about the topic. Depending on the class’s prior knowledge and experience, this skill can be embedded in a project or specific task, or can be specifically taught, by setting up a topic for ‘research’ and walking students through the necessary steps.

Even when students are back on-campus, these elements of online learning will still be useful and can be done either in-class or at home, so long as they are an integral part of the teaching and not just added on as extra work.

Limitations of online learning

‘Hands-on’ work

Practical work requiring specialised equipment (i.e. equipment not easily or regularly available at home) or requiring supervision for safety reasons or requiring ‘hands-on’ practice to get results, is often difficult to do online, although videos or online simulations may help. Increasingly such material is freely available online but for most practical work it is probably more useful used in conjunction with rather than replacing hands-on experience.

I would also include ‘performance’ areas, such as art, drama, and music, as difficult to substitute fully with online learning. Again, some aspects can be done just as well online, but ‘satisfying’ performance usually needs people to perform together in real time – and a live audience. Of course we have seen many brilliant examples during Covid-19 of online performance. However, it is not a replacement for live or hands-on performance; it is different, and an art form in its own right.

In an emergency, it may be possible to rethink practical work so it combines resources available both at home and online but this will probably require considerable redesign. Nevertheless, in core subjects such as science, it might be worth considering an alternative online curriculum that could be used during an emergency.

Social development

One very important function of a school is the social development of a child, particularly in the early years. This is really difficult to replicate online. Children benefit from mixing with children from diverse backgrounds. Children need to mix, touch, argue, be surprised, in real time with other children, and with preferably an adult as supervisor to ensure things don’t get out of hand or to set standards of acceptable and unacceptable behaviour, and (more positively) to provide the love and encouragement that young children need in their early development.

Parents obviously play this role at home, but the value of school is that it locates such development in a context wider than the immediate family.

More work all round

Without (and often even with) special training and course redesign, teaching online is going to be more work for teachers, parents and even children. It requires rethinking teaching methods, and doing things quite differently from in-class, for it to be successful. This is probably the most serious limitation of online learning.

The way to avoid this is through better pre-service and in-service training in online teaching, the preparation of alternative curricula in advance of an emergency, and better technology support for teachers, parents and students. This of course all costs money, and is an issue I will address in more depth in the next and last post in this series.

The ‘intangibles’

There are several other less easy to define or measure but still important intangibles about school that cannot easily be replaced by online learning. You are probably better at identifying or expressing these than I am but here are some I would include (and some you may see as negative rather than positive):

- the inspiration of an excellent teacher (but could that not be replicated online?)

- the discipline of getting up and going to school every day

- getting away from the rest of the family

- making, meeting – and losing – friends

- extra-curricular activities such as sports, concerts, drama

- meals for children from poor families

- security for children from abusive parent(s)

- and so on

Nevertheless, while there are some serious limitations to online learning, they are not as many as one might think. Many of the core activities in academic learning can be achieved as well if not better online. The limitations lie more in the non-academic aspects of schooling, the lack of training/experience of teachers in online learning, and the need to rethink curricula and teaching methods. In particular, the age of children is critical: the younger the more difficult it is for online learning to replace the essentials of the school experience.

Conclusion

My aim here is not to argue for the replacement of campus-based schooling with online learning, not even in the higher grade levels, where most academic activity, at least in non-STEM subjects, could be done just as well online.

However, I am arguing three main points here:

- there are benefits in using online learning much more in regular school teaching to supplement and extend classroom activity, as long as the curriculum is redesigned and the online work is integrated into the curriculum and not just added on;

- there would be a benefit in considering/preparing an alternative online curriculum for use in an emergency;

- there are limitations in online learning, but they are less than is generally assumed by parents and teachers; so better communication to parents and teachers (and politicians) of the merits and limitations of online learning is also probably needed.

Up next

Ministry and school board policies for online learning.

Teachers and parents

What are your views on the strengths or limitations of online learning? Do you have something different to add? If so, please use the comment box at the end of this post – I’d love to hear from you.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

I think it gets even more difficult in K12 vocational schools, mainly with technical subjects, such as Cooking techniques, for example.

And the vocational students are, in general, hands-on-the job kids.

But imagination and motivation must be in the heart and mind of these teachers.

From March to July our students produced very interesting projects and we were very proud to see that all our effort was worth it.

Many thanks, Célia. Fully agree with you. Jamie Oliver does pretty well with his television series on cooking!

Do you think that changing the online teaching environment from a 2D one to a 3D (VR) one would be beneficial? VR has lots of affordances mainly helping with removing the limitations of online learning that you mentioned.

Thanks, Cristina.

Yes, certainly VR has great potential in teaching. The main issue is cost and the need for expertise in production. Headsets are also an additional expense, so the cost per student use is still quite high. One solution would be for school boards to collaborate to produce VR that could be shared across the system to deal with common learning difficulties (I’m thinking here of calculus and statistics!), preferably as OER. The biggest problem though would be training teachers in how to use such technology for teaching, because usually the VR experience needs to be integrated with teaching and learning in general. Neverthelss I think that if used selectively, VR has great potential