I am writing an autobiography, mainly for my family, but it does cover some key moments in the development of open and online learning. I thought I would share these as there seems to be a growing interest in the history of educational technology.

Note that these posts are NOT meant to be deeply researched historical accounts, but how I saw and encountered developments in my personal life. If you were around at the time of these developments and would like to offer comments or a different view, please use the comment box at the end of each post. (There is already a conversation track on my LinkedIn site).

Satellite TV in India

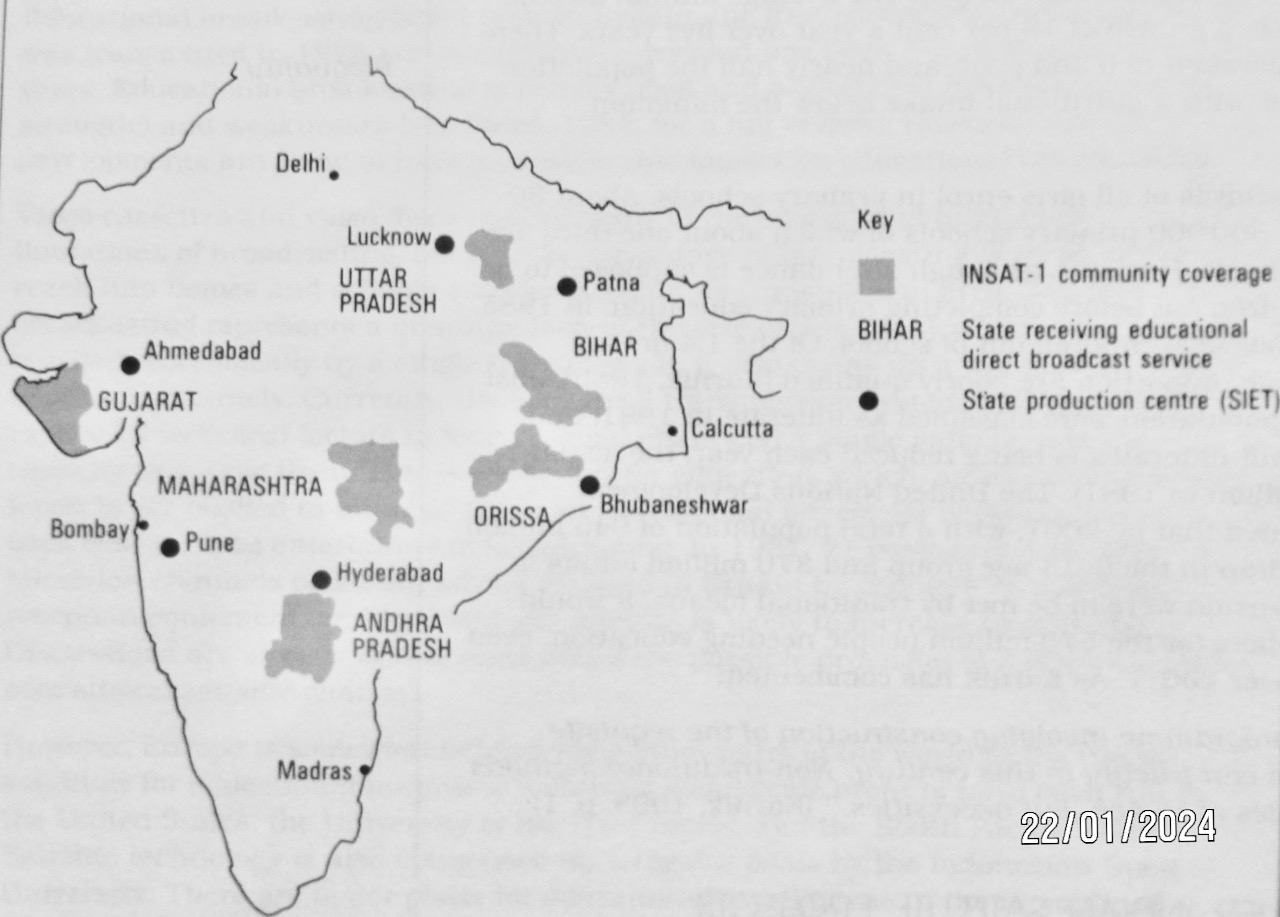

Towards the end of the 1980s, there was growing world-wide interest in the potential of satellite TV for educational purposes. India was one of the pioneers in using satellite TV in education. As early as 1975, the Indian Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE) had used the American ATS-6 satellite (the same one as used by the Appalachian Educational Satellite Project) to broadcast natural science programs to children and 44,000 teachers in primary schools in 2,330 villages across less accessible parts of India. Each target village was provided with a television set and low cost dish aerials and convertors, located in a communal centre in the village. The courses were developed by the National Centre for Educational Technology in Delhi (NCET). The programs were developed in four of the different languages used in the target areas. The satellite allowed for several audio channels so the villagers could choose the appropriate language.

The project was extensively researched and evaluated. Programs were usually viewed in the open air, with audiences of around 100 per village per evening, with about one third children. Almost a quarter of those who viewed the programs had never before heard radio or seen a film, nor read a newspaper.

The program however was an experiment and lasted less than one year. (The Americans wanted their satellite back). However, the Indians did not give up. In 1982 they began their own program, launching a series of national satellites used for radio and television tranmissions, telecommunications and weather forecasting. By this time, the NCET was broadcasting a wide range of programming to schools across the country, using a mix of terrestrial and satellite communications.

In 1986, I was working as a block co-ordinator on an Open University joint Social Science and Technology course (DT200). This block of four weeks study time for students was on information technology in education and training. Part of the block was on satellites for education and development, and the BBC proposed that they should send a team to India to make a TV program to go with the printed material. As the subject expert, I was asked to be the presenter and do the interviews in India.

A keynote in the Himalayas

I had been in India just the year before. I had been invited by the Indian University Grants Committee to give a keynote at their annual conference. The topic requested was on research on the the use of television for teaching in higher education. It would be held at the Himachal Pradesh University in Simla, at the foot of the Himalayas. All expenses would be covered.

On June 25, 1985, I flew British Airways from London to Delhi. When I landed in Delhi, I found the usual chaos, but even for India, the chaos this time seemed unusually elevated. The airport was full of soldiers and police wielding their lathis, a heavy bamboo baton, and people rushing about, and some large groups holding and hugging each other. Nevertheless, I headed for the main bus station in Delhi, where as directed I caught the express bus from Delhi to Simla.

It was extremely hot, but I found a window seat with an open window. It was going to be a long, ten hour journey through the Punjab. Towards the end of the route, the road started to climb up into the Himalayan foothills. The road got narrower and more winding, with an increasing number of hairpin bends. When I looked out the window, I often could see no road beside the bus – just the bottom of the valley several thousand feet below.

When I got to Simla, there was someone waiting for me at the hotel.

‘Dr. Bates? Thank goodness you’re all right!’ he exclaimed.

‘Yeah, it’s a pretty scary road. Thanks for your concern.’

‘No, no, no, sir. It’s not the road. Haven’t you heard?’

‘Heard what?’

‘There’s been a terrible air crash.’

I had been flying the same day as the Air India terrorist bombing, which was the worse terrorist act before 9/11 – over 250 passengers from Montreal to Delhi were killed by a bomb placed by a Sikh nationalist based in Canada. That explained the chaos at Delhi airport.

I was more concerned than usual about my presentation. It depended heavily on a series of examples of the use of television for teaching which I had assembled on a VHS video cassette. In 1985, there were still two competing standards (VHS and Betamax) and also national television standards varied. I had asked about this before leaving England and had received assurances that all the technology requirements would be met in Simla. But….

My anxiety was not helped when the man who met me at the hotel said, ‘Sir, this is a very important conference. The Vice Chancellors from nearly all the universities in India will be present. They are all very much looking forward to your presentation.’

The conference was to last five days and I was speaking on the last day. On arrival at the university, I immediately asked to see the technical person responsible for the presentations. Eventually a rather harassed man was introduced to me.

‘I need to test the equipment before my presentation. Can you give me a time when I can access your video cassette player and its connection to the video projector?’.’

‘Of course, sir, everything will be good.’

‘Yes, but I would still like a time to test the equipment first.’

‘Of course, sir, I will let you know as soon as I have a time for you to test it.’

‘Why can’t you give me a time now?’

‘Oh, I am very busy. I will give you a time after today’s sessions.’

This conversation was repeated every day for three days. I finally lost my temper.

‘My presentation’s tomorrow at 9.00 am. I insist that you let me try the equipment out.’

‘I am so sorry, sir, but we do not have a video cassette recorder and projector in the university. We need to hire the equipment from a store in town, and we have only the money to hire it for one day. It will be coming tomorrow morning.’

‘Dear God, the conference organisers have paid for a return airfare from England and five nights at a four star hotel, and you can’t afford to rent equipment for more than one day?’

‘I am very sorry, sir, but it will be here at 9.00 am tomorrow, on the dot. You will be able to test it then.’

‘But what if it doesn’t work? What do I do then?’

‘Oh, sir, rest assured, they are a very reliable company.’

Like most universities, Himachal Pradesh University was a little out of the centre of town, about a 15 minute walk up the hill from his hotel. As I was walking up the hill, I heard lots of shouting.

‘Look out, sir,’ a man running down the hill shouted at me. ‘It’s the baboons.’

Sure enough, there were about a dozen large baboons coming out of the trees at the side of the road about 100 metres ahead, with several men wielding sticks and yelling at them. Eventually someone threw some food into the trees and the baboons retreated, leaving the road clear.

I at last arrived at the lecture hall, a few minutes later than I intended. There, sitting on a table in front of the podium, was a cassette recorder and projector. When I entered the cassette, it played perfectly. Many times in my career, the lecture theatre technicians have pulled through and saved the day, often at the very last minute (although once in Germany, I was told by a technician that: ‘In Germany, we do not do Apple.’ And that was that – no slides.) But….

Just before my presentation was due to start, the chairman of the conference organising committee was to speak for a minute or so, thanking everyone for their help with the conference. In fact, he took nearly 30 minutes, so I started 30 minutes late. I was halfway through my talk when there was muttering behind me and the man chairing his session said through his microphone: ‘Dr. Bates has to stop now. The equipment needs to be returned.’

Apparently, the equipment had been rented for only two hours, and needed to go back down town. There was uproar.

A very distinguished man rushed onto the stage (he was one of the Vice-Chancellors).

‘This is ridiculous,’ he said. ‘Dr. Bates has come all the way from England to give his talk. How much to rent the equipment for another two hours? I will personally pay for this,’ he said, waving a chequebook.

After a minute or so of consultation between the technician. the Vice-Chancellor and several others on the organising committee, the chair of the session approached me.

‘Please continue,’ he said. ‘Everything is in order.’

I finished my talk and the equipment was swept up and disappeared down the hill and everyone was happy.

You can land a man on the moon – but can you get a beer?

So, it was with some trepidation that I set out a year later with a BBC video crew to Ahmedabad, where the Indian Space Research Organization was based.

Once again, when I arrived with the BBC film crew, it was exceedingly hot. We checked into our hotel and the BBC producer said to me, ‘We’re going out to scout some locations for shooting. No need for you to come, but can you get us some beer for when we get back?’

‘No problem,’ I said – but I was wrong.

Ahmedabad is in the Indian state of Gujarat. It is a dry state. The sale of alcoholic liquids to the general public was prohibited. A hot BBC crew without access to alcohol is a dangerous beast to work with. So I went down to the hotel reception and asked where the nearest place was to buy beer. The receptionist started shaking his head.

‘Sir, you need a liquor permit.’

‘No, I don’t want to sell beer – I want to buy it.’

‘Sir, buying alcohol in Gujurat is strictly against the law. But you are a foreigner so you can get a permit.’

‘Good – where do I go to get one?’

‘Sir, the nearest state home department is 15 minutes walk from the hotel. I have a map.’

I headed off and eventually found the office just off a busy highway. When I entered, there was a counter with a man behind it.

‘I’d like to get a liquor permit please, I am British,’ I said, waving my passport.

‘Yes, sir. Here’s a ticket. Please wait over there,’ he said, indicating a set of chairs in a large-ish space behind him. There were about 15 people waiting. At last my number was called. I went to another table behind which were two men.

I gave the first man my passport, who looked at it then passed it to the second man, who wrote something down in a large ledger, then returned the passport to me.

‘I also need a letter stating your purpose in visiting Gujurat.’

‘But I don’t have one with me – it’s back at my hotel.’

‘I am very sorry sir, but without such a letter we cannot issue you a permit.’

So I trudged back to the hotel, and found a copy of the letter from ISRO, welcoming me and the BBC crew to visit. By this time the sun was really up and it was even hotter but I walked back to the state home office, again was given a ticket, again waited 15 minutes then went to the table with the same two men.

I showed the first man the letter and he passed it to the second man who went away and photocopied it and returned the letter to me.

‘Now I need two passport photos of yourself, please.’

I groaned. ‘I don’t have two passport photos with me.’

‘I’m sorry, sir, but we must have the photos for a permit. There is a store down the road where you can get your photo taken.’

So once again, I trudged down the road, with it getting even hotter, and got the two photos taken and returned to the state home department office, got a ticket, waited another 20 minutes, and finally arrived back with the same two men behind the table. The first man took the two photos then passed them to the other man. He then produced a sheaf of papers and passed them to me.

‘Please take these papers and your passport and visa to the room over there,’ he said. I had not noticed that at the back of the waiting room was another door. I went in.

Again, there were two men, one waiting at the door, and another behind a large desk. The man at the door took the sheaf of papers and the passport, looked at them, gave them back and nodded to the man behind the desk, who took the papers off me, returned my passport, then took a large stamp and banged it down on a sheet of paper, which he handed to me.

‘This is your liquor permit. Show it whenever you need to buy alcohol. It is valid for seven days.’

I then flagged down a taxi and asked him to go to the nearest liquor permit store where I bought a dozen Indian beers and took the taxi back to the hotel.

When the crew arrived back in the late afternoon, the first thing they said to me was: ‘Where’s the beer?’

‘I’ll go and get it – there’s no fridge in the rooms.’ I went to the hotel kitchen, where I had stored the beers in a large refrigerator. I returned with the 12 beers, which the five of us dispatched very quickly.

‘OK,’ said the cameraman. ‘I’ll get some more. Where did you get them?’

I sighed. ‘Just go to reception. He’ll tell you.’ It was easier than explaining. But now, as the only one with a liquor license, I had some measure of control over the crew.

The outcome of the visit

We eventually made the television program with tremendous help and support from ISRO at their headquarters in Ahmedabad, and went to a village where programs were being watched. We viewed a number of the programs made for broadcasting, and came away with a much stronger understanding of the challenges and achievements faced in using satellite broadcasting for development. The DT200 course unit, which contained extensive engineering information about satellite technology as well as a discussion and analysis of its educational use, concluded:

‘There are some lessons for the application of satellite technology for educational purposes:

- clear educational objectives and priorities, linked to clearly identified educational needs

- comprehensive local ground support (reception equipment and maintenance, viewer recruitment and management, etc.)

- separate programming in different languages

- high quality educational content suitable for continent-wide distribution.’

Today

India has successfully launched 40 communications satellites so far and was using satellite broadcasting for education up until 2014. It now has a wide range of terrestrial educational broadcasts.

Up next

My next post will be on Satellite TV in Europe and the lessons learned during the 1980s about the conditions necessary for the successful use of technology in education.

Further reading

Agrawal, B. (1983) The socio-political implications of communications technologies in India, Media Development, Vol. 30, No.4

Agrawal, B. et al. (1984) INSAT Pre-production Television Research for Higher Education Ahmedabad: ISRO

Banarjee, S. (1984) Television for rural development – A scrutiny of the INSAT promise Patriot, March 4

Jayaweera, N. (1983) Communication satellites: a third world perspective, Media Development Vol 30. No. 4

Karnick, K. (1985) A Systems Approach to Satellite Delivered Learning: Some Indian Experiences, Stockholm: 36th Congress of the International Astronautical Federation

UNDP (1984) Establishment of a Central Institute of Educational Technology (INSAT for Education) New Delhi: Government of India

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Wht a lovely and funny India story, Tony!

Thank you for sharing your experiences. I enjoyed reading it. Things have marginally changed ever since locally, though India has progressed well in the IT and telecom sector.