The challenge

On balance, although there are many shortcomings and issues, the post-secondary/higher education level has managed relatively well in finding alternatives to in-class teaching and moving most if not all teaching fully online.

The k-12 systems though have not managed as well. There are good reasons for this, and I do not envy anyone in the k-12 sector who has to cope with the challenges of Covid-19. There are no really good solutions, only those that are less bad than others. The issue is not what was done in March, when there was no time to prepare for the closing of schools, but what is happening now, nearly a year later.

If the media reports I’ve been reading are accurate, there are still some major shortcomings in the provision of online learning in the k-12 sector. I believe much more could be done to improve the way that online learning is being deployed in k-12 systems during the pandemic, and this will have important lessons for online learning in schools after the pandemic.

Parents have multiple concerns:

- a conflict between the health risks of sending their children to school with other demands, such as the need to go to work if they are essential workers, or combining work from home with supervising their children’s studies;

- the perceived shortcomings of online learning;

- confusion about their role in supporting their children’s learning at home.

Teachers are concerned about being unsupported when teaching online, in some cases threatening to strike over safety issues or going absent to protect their own families, and teachers certainly feel stressed and overworked, especially if they are teaching both face-to-face and online simultaneously. Above all, effective practices in online learning are not being followed in many cases.

So I will be putting forward some suggestions about what could be done to improve the use of online learning in the k-12 sector, both during and after the pandemic. I do this with some trepidation for reasons that will become clear. This topic will also take more than one post, as it is a complex issue, because the challenges for the k-12 sector are indeed much greater and more difficult than for the post-secondary sector.

Am I qualified to contribute to the discussion?

I also worry about whether I am qualified to raise such issues. My work and experience in online learning is almost entirely at the post-secondary level. I haven’t taught online in the school sector. There are other specialists in online learning in the k-12 sector such as Randy LaBonte of CANeLearn, Michael Barbour of Touro University, California, and Robert Martellacci of Mindshare, Ontario, who are better qualified, and I have drawn on them for advice and feedback for these posts, but nevertheless the views expressed here are solely mine.

However, I am a qualified teacher who has taught in both elementary and secondary schools, even if long ago. I know therefore that there are significant differences between the sectors, mainly in terms of resources, but also in what is a really important issue here, centralisation vs decentralisation of policy and implementation. I also have over 40 years of experience in teaching, managing and evaluating online learning.

Nevertheless, much of what I will be proposing will be more based on principles and theory than on practice. I don’t have solutions that I can put my hand on my heart and say from personal experience, ‘I know this will work.’ What I want to do instead is to provoke a discussion among stakeholders in the school systems about alternatives to some of the current policies and implementations of online learning that I truly believe are failing the school sector.

Agency and stakeholders

When looking at k-12 online learning, it is important to appreciate the wide range of agencies with direct responsibilities for decision-making, and stakeholders with interests:

- state and provincial ministries (in some countries, federal or national governments also)

- school boards/regional jurisdictions

- school administrators

- teachers

- students

- parents

- province-wide agencies, such as BC’s Open School (public), and Ontario’s Virtual High School (private).

One might also add employers, unions and other external agencies. During pandemics such as Covid-19, Ministries of Health are other important stakeholders/agencies.

When making decisions about online learning, most of these stakeholders need to be involved or at least consulted, but agency (responsibility for making decisions) may be much more limited.

However, it is important that online learning issues are decided at the most appropriate level of decision-making. This I believe is one of the main problems we are seeing in the k-12 sector: certain kinds of decision involving online learning are being decided without those with expertise in online learning being at the table or listened to. I will discuss this in more detail in later posts.

First though we should look at the state of online learning in school systems before the pandemic hit. I will focus here on Canada, although some of the issues will apply to other countries as well.

Canada Pre-Covid

Online course offerings and enrolments

Each year, CANeLearn provides critical information and insight into how Canadian educational authorities and governments are integrating technology-supported approaches to prepare students for today’s economy and a future society in which the use of technology will be ubiquitous.

In their 2019 report, CANeLearn reported that every province and territory in Canada offered at least one online program in the k-12 sector, except for Nunavut and Prince Edward Island. Ontario had the most programs (up to 84) with British Columbia (a province with a third less population) close behind with 74. Manitoba (38) and Albert (33) were next in number.

In terms of level of distance and online learning activity across Canada, the number of students engaged in K-12 distance and online learning in 2019 was estimated by CANeLearn at just under 300,000 or almost 6% of the overall K-12 student population. Ontario (89,000), Alberta (76,000) and British Columbia (65,000) had the highest number of online enrolments.

Who are the students?

Most fully online programs are targeted at Grades 10, 11 and 12 (15-18 year old) and are for the most part optional, often taken by students in schools without a specialist subject teacher or students who have difficulty in accessing school on a regular basis. However, Ontario mandated in the fall of 2019 that all students must take a minimum of two e-learning credits out of the 30 credits needed to fulfill the requirements for achieving an Ontario Secondary School Diploma, although parents can still opt out if they wish.

Blended learning – a mix of classroom and online work – is also growing rapidly in Canadian schools, and extends right down to elementary school level. Blended learning is much harder to track though.

Governance

Provincial governments through their Ministries of Education have overall responsibility for k-12 education in Canada. CANeLearn reports:

While many provinces and territories continue to have some reference to distance education in the Education Act or Schools Act, in most instances these references simply define distance education or give the Minister of Education in that province or territory the ability to create, approve or regulate K-12 distance education…. The most dominant trend affecting the regulation of K-12 distance and online learning is that approximately a third of all jurisdictions use policy handbooks to regulate K-12 distance and online learning; sometimes in combination with a formal agreement or contract.

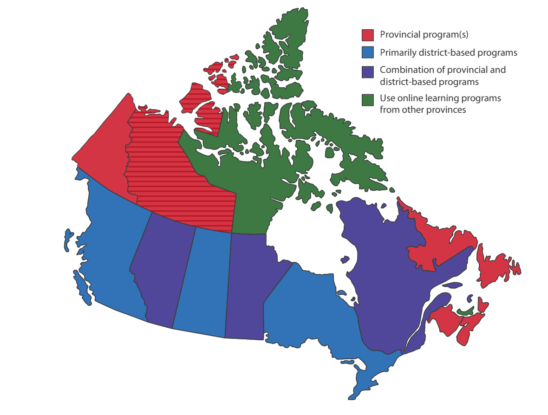

What complicates matters is the role of locally elected school boards, who in practice are generally responsible for the offering of online courses. Most jurisdictions continue to have either primarily district-based programs or district-based programs and provincial programs, with the exception of the smaller-populated Atlantic and Northern provinces/territories, where most have a province-wide agency.

Although school boards must follow Ministry regulations, these in general leave a fair degree of autonomy to school boards. School boards can draw on centralised services, develop their own online courses, and provide the teachers for such courses. Lastly, in some provinces there are boards for religious, private (commercial) and minority languages running parallel with the public school boards, so there is often competition for students, both in schools and online. In Canada, online courses provided by public school boards are usually offered free.

In practice, then, there is considerable variability in the organisation and management of online learning in Canada, as illustrated in Figure 1 below:

Online course development and services

In general, although school boards in Canada offer their own online courses, often these are developed and supported externally. For instance professional online course development, and support services for online teachers, are available through the Western Canadian Learning Network, a consortium of school districts within BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, the Yukon, and NWT, who work together to support blended and fully online courses and teachers. Most teachers on these courses are regularly employed, fully qualified teachers working for their respective school boards, although the design and development of the course may be done centrally. School boards pay a fee to join, which varies by the number of enrolments in the courses.

Ontario has a number of centralised services. The Ministry of Education provides a list of courses available in each school board through its eLearning Ontario web site. The Ministry hires teachers in the summer to write many of these courses. Through the Ministry’s EduGains site, teachers, students and school board administrators can access a wide range of resources to support online and blended learning, including the province’s own Virtual Learning Environment, based on D2L’s Brightspace. These resources range from fully online courses from Grade 9 through Grade 12, to ‘stand-alone’ digital resources that can be used from elementary to high school level in both the classroom or online by students. Thus although school boards and teachers in Ontario have a good deal of freedom to manage their online teaching, there are many centralised or province-wide resources on which they can draw.

Most online courses offered through school boards will have a standard learning management system within that school board area, and as long as 15 years ago, some provinces bought licenses for synchronous conferencing systems such as Elluminate Live. Nevertheless there can be considerable variety between school boards even within the same province in the provision of online resources.

A well-established infrastructure

The important point here is that online and blended learning in the k-12 sector was not invented for Covid-19. It had been widely practiced in Canada for at least the previous 20 years, so there was considerable experience within the country prior to Covid-19.

How well has this experience been used during Covid-19? That will be the focus of the following blog posts.

Up next

The next post will look at technology access and the implication for choice of technologies for online teaching. Other posts will cover the following topics:

- teaching foundational skills online

- the need for a different curriculum for learning from home

- the role of parents

- policies for government, pandemic and post-pandemic

- strengths and weaknesses of online learning for the k-12 sector

- what next

References

Barbour, M. and LaBonte, R. (2019) State of the Nation:K-12 eLearning in Canada:2019 edition CANeLearn

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.