The issue

Institutions are struggling to define online or digital learning for their students. In particular, students need to know whether a course requires attendance on campus, whether they need to be online at a set time, and what kind of course it will be (fully online, blended/hybrid, or fully in-person, or available in any of these formats (HyFlex). Thus the naming of the type of course is important, as well as students’ understanding of that naming.

Secondly, online learning has several well-established sets of quality assurance standards, for instance, in North America the Quality Matters (QM) standards, which cover higher education, k-12 and continuing and professional education. These were established well before the Covid-19 pandemic, and were heavily used in developing asynchronous online learning courses and programs. However, in general, these quality standards were totally ignored as institutions moved to emergency remote learning, using primarily synchronous, video-streamed lectures.

This would not have mattered if there were in place and widely used quality assurance rubrics for in-person teaching, but although some standards exist, they are not widely followed, at least in a formal sense, and they were certainly not obvious in much of emergency remote learning.

This raises a number of questions:

- can we have consistent definitions for the various delivery methods now available so students know exactly what they can expect before enrolling in a course, and so there is some commonly agreed terminology when discussing online and blended/hybrid learning?

- are the existing quality assurance standards and rubrics for online learning appropriate for all forms of delivery, including in-person teaching and/or synchronous online learning? Or do we need different quality assurance rubrics for different forms of delivery?

- why in the past have we expected quality assurance standards to be applied to online learning but not to in-person teaching?

The following post attempts to explore these questions.

Defining the delivery of teaching

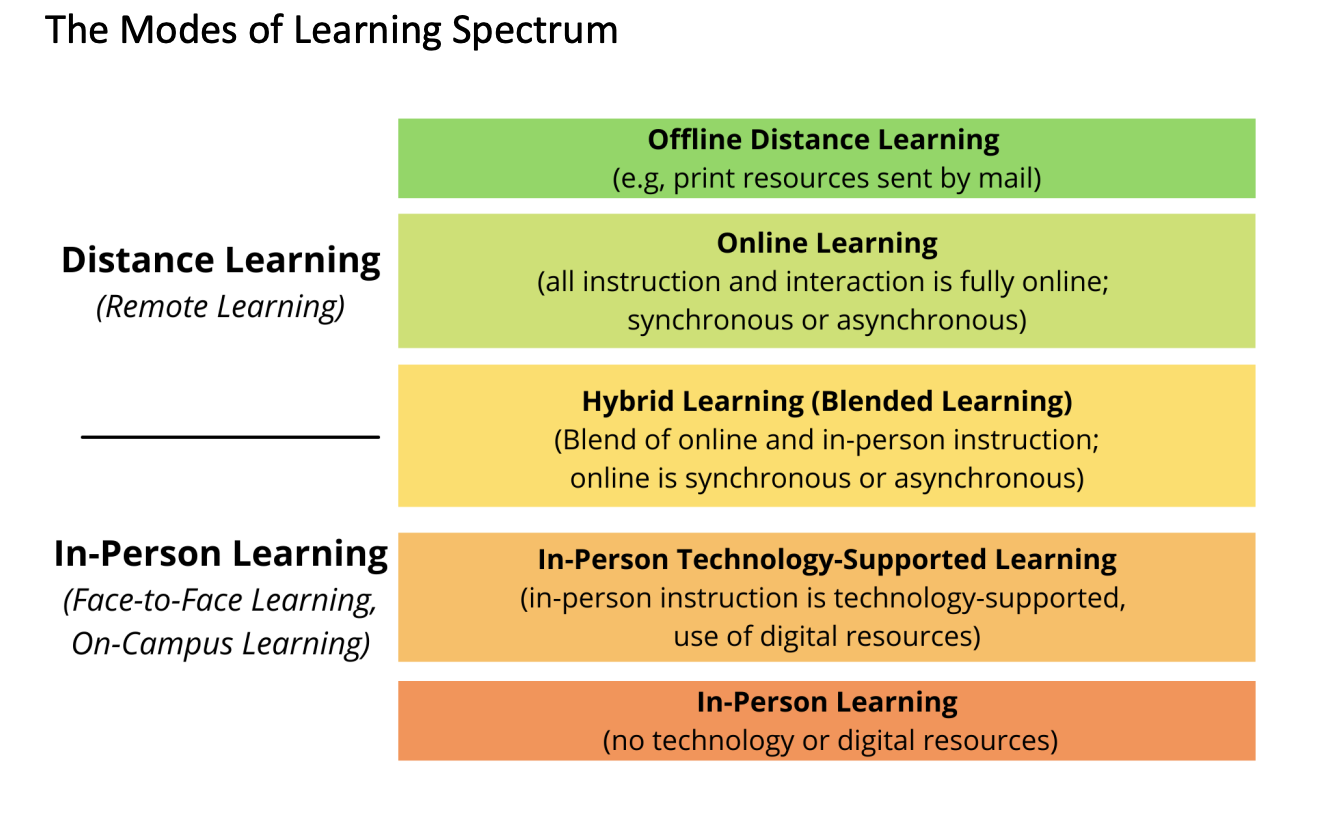

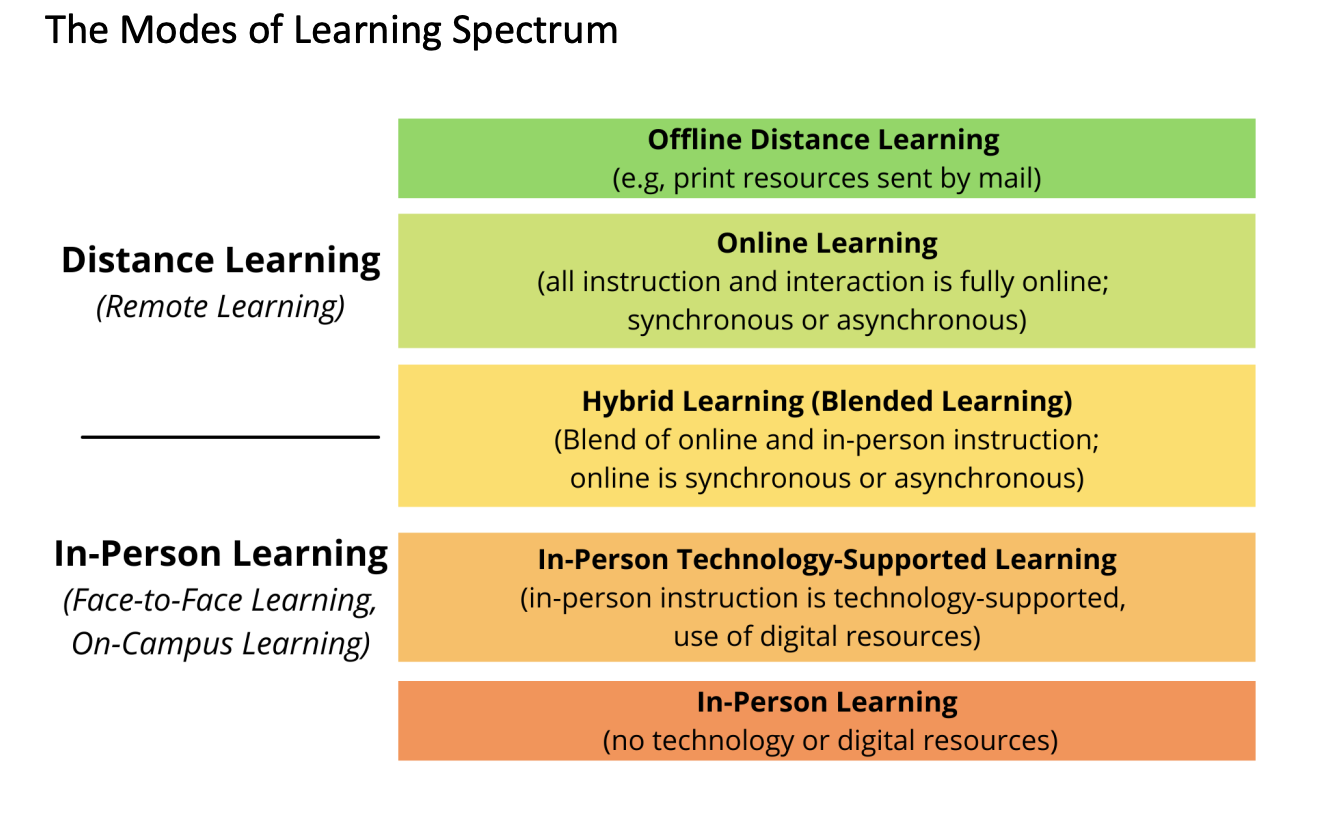

WCET and Bay View Analytics in the USA and the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (CDLRA) are both working in collaboration to develop a set of definitions that can be commonly used across their higher education systems.

The CDLRA has surveyed Canadian post-secondary institutions on their existing definitions, and has developed a recommended set of definitions (Johnson, 2021)

There are four things to note about these definitions:

- the first is that they are comprehensive, in that they cover the full range of possible delivery modes or methods, not just online learning;

- however, the CDLRA definitions do not have separate categories for synchronous and asynchronous online courses, and this is an important distinction for both instructors as well as students

- the definitions do not include HyFlex courses, i.e. courses that are offered in all of these versions

- hybrid learning itself covers widely differing types of courses; it is a rapidly emerging phenomenon, under constant change as instructors explore various ways of combining in-person and online learning.

Nevertheless the CDLRA definitions are an important step in bringing clarity to the definition of courses. As well as enabling students to understand the different types of courses on offer, the CDLRA definitions also enable the CDLRA to track the balance of delivery modes across institutions in any one year, and thus track emerging directions for digital learning in Canada.

In another recent publication, Robert Ubell (2022) challenges the use of synchronous and asynchronous because they are etymologically Ancient Greek words and do not ‘resonate’ with instructors and students. He proposes ‘online’ instruction as a substitute for synchronous and ‘offline’ for asynchronous. However, Joshua Kim (2022) responded by saying ‘It seems strange to call what is mostly done in online classes—reading articles, watching videos and participating in discussion boards—”off-line”.’ Also, in-person teaching is also synchronous, so it makes no sense to call it online. I’m afraid Robert Ubell’s attempt at re-definition merely confuses an already overly complicated situation. We should not be scared of using words that derive from Greek, such as pedagogy, and asynchronous is more succinct than ‘in different places and at different times’. More importantly, asynchronous learning allows students to study at their own time and pace and that is a very important distinction from synchronous learning, whether online or in-person.

In summary, my view is that we build on the CDLRA definitions, but also emphasise the difference between synchronous and synchronous online learning, and also add HyFlex as another form of delivery. On the other hand it may take many years if ever to agree on a standard definition of hybrid learning – which may not be a bad thing, as it allows for innovation.

The issue of quality

In a sense, while definitions and a common understanding of terms are important, what tends to cloud the issue are questions about the quality of various delivery modes. There is often an implicit judgement from instructors and often students that one method or mode of delivery is inherently superior academically than another, and in particular that in-person teaching is superior to other modes of delivery. I also have a bias in favour of asynchronous over synchronous online learning, mainly because it better suits students who choose online learning for its flexibility.

Let me say from the start though that I believe any of the modes of teaching can be done well, provided that the right conditions are met, i.e. they meet quality standards. If we can assure quality standards for all forms of delivery, which I believe we can, then what should matter is the extent to which a particular delivery mode meets the needs of different students.

For instance, working professionals or single mothers are more likely to want the flexibility of asynchronous online learning, and novice students straight from high school are likely to want and need the benefits of in-person teaching. This should be the standard by which decisions about mode of delivery should be judged by. It should not matter how the courses are delivered; the quality should be good in any mode.

How general are quality assurance standards?

Standards such as Quality Matters were deliberately designed originally with asynchronous online courses in mind, based on research and best practices (defined as practices leading to quality learning outcomes). However, if we look at for instance QM’s General Standards, they would apply to most modes of teaching:

- Course Overview and Introduction

- Learning Objectives (Competencies)

- Assessment and Measurement

- Instructional Materials

- Learning Activities and Learner Interaction

- Course Technology

- Learner Support

- Accessibility and Usability*

These all need to be in place within a course and aligned (e.g. assessment must be aligned with learning objectives). Also each of these general standards can themselves vary in quality. There is a wide variety of quality assurance standards, some of which go into considerable detail. Nevertheless, a course that lacks any or all of these eight general standards would fail QM’s quality assurance process.

Before Covid-19, most institutions in North America offering online courses for credit followed such quality standards either explicitly or implicitly, through online course design, usually based around an asynchronous online learning management system, which had many of these standards built into the software.

Quality standards for synchronous teaching

As I said, there is no reason why these standards could not be applied to synchronous teaching, either online or in-person. However, looking at much of the research on synchronous online learning during the pandemic, it seems clear that these quality standards were often lacking. In particular, learning activities, learner interaction, learner support, and accessibility/usability were often missing in action.

Why was this? For two reasons:

- these quality standards are rarely applied, at least explicitly, to in-person teaching, or more accurately, to large lecture classes

- even where they were applied to in-person teaching, they were not sufficiently or adequately adapted when in-person teaching methods were moved to synchronous online learning.

This was understandable in March, 2020, when the pandemic forced everyone to move to online delivery; it is not acceptable though now in 2022. If courses that were formerly in-person are now being delivered online, they need to meet quality assurance standards.

The issue then is not whether or not to have quality standards for synchronous online learning, but what those standards should be. Should they be the same as for the previous asynchronous online courses, or should they be different? My own view is that probably the previous general standards for online learning apply just as much to synchronous, but there may be additional standards needed to take account of the synchronicity. More importantly, there should be clear quality standards based on research and effective practice for synchronous online learning.

This of course raises the question then of why there are not quality assurance standards for in-person teaching. In fact, it is possible to identify quality standards for in-person teaching. Chickering’s seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education were developed as long ago as 1987:

- Encourages contact between students and faculty

- Develops reciprocity and cooperation among students.

- Encourages active learning.

- Gives prompt feedback.

- Emphasizes time on task.

- Communicates high expectations.

- Respects diverse talents and ways of learning.

Donald Bligh’s research on the effectiveness of lectures (2000) found that in order to understand, analyze, apply, and commit information to long-term memory, the learner must actively engage with the material. In order for a lecture to be effective, it must include activities that compel the student to mentally manipulate the information.

Why then are such quality standards for in-person teaching rarely applied except on a voluntary basis by individual instructors? The main reason is that online learning, both synchronous and asynchronous, is recorded. It is possible to evaluate reasonably objectively whether standards have been adequately met. Most in-person teaching is not formally recorded or externally assessed, other than through student ratings, which are notoriously unreliable as a measure of quality. However, if it was thought important, in-person teaching these days could be recorded and evaluated, using lecture capture for instance. However, many faculty would object, citing interference with academic freedom.

What this means of course is that we have had for many years a double standard for teaching: online learning must be more rigorously evaluated than in-person teaching. However, Covid-19 and the move to synchronous online learning, which mainly transferred in-person teaching methods to online delivery, has made it apparent that quality has little to do with mode of delivery but more to do with the quality of the teaching used within the delivery mode.

So, yes, we should have quality standards for all modes of teaching. Many of these will be common, but there will be additional standards required for specific modes of delivery. I look forward to this development for in-person teaching.

For more discussion of this issue tune into WCET’s Virtual Summit on Elements of Quality Digital Learning on April 6. For more details, go to https://pheedloop.com/wcetsummit2022/site/home?org=1741&lvl=100&ite=1821&lea=485224&ctr=0&par=1&trk=a1E8V00000F9iI3UAJ

References

Bligh, D. (2000) What’s the Use of Lectures? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Chickering, C. and Gamson, Z. (1987) Seven Principles For Good Practice in Undergraduate Education Washington D.C: American Association for Higher Education

Johnson, N. (2021) Evolving Definitions in Digital Learning: A National Framework for Categorizing Commonly Used Terms Ontario: Canadian Digital Learning Research Association

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Excellent review of the issues.

Re the US, people in Canada might want to look at the NCHEMS/C-RAC quality guidelines, which seem to be accepted by the Regional Accreding Bodies in CHEA – https://nc-sara.org/news-events/information-about-21st-century-distance-education-guidelines – whereas Quality Matters are not so integrated at that level.

By the way, what happened to the earlier CANReg guidelines, did they affect any provincial quality schemes for universities or get built into good practice in institutions?

I also see British Columbia (and maybe in other provinces too) guidelines for K-12 online – Standards for K-12 Online Learning in British Columbia, Version 3.1, British Columbia Ministry of Education, July 2021, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/administration/kindergarten-to-grade-12/online-learning/ol_standards_k12.pdf – would some not apply to universities? (shocking thought)

Thanks for your comment, Paul. Very much welcomed.

I hope colleagues in Canada will answer some of your questions, because provincial governments generally devolve quality assurance measures to the institutions. Certainly here in BC, several institutions do have quality assurance guidelines for faculty for online learning or the application of educational technologies. The BC College system at one point had a voluntary system of external formal review of programs in which was embedded a set of quality assurance guidelines as part of the assessment process, but to be honest it is still very much an individual institutional policy here. However it is still a lively source of debate. For instance WCET has a webinar today on quality assurance in a post-pandemic age.