Zawacki-Richter, O. and Jung, I. (2023) Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Learning Singapore: Springer

Part III of this open textbook is on Global Perspectives and Internationalization, and is the second part of the Macro-level perspective. I have already reviewed Part II, on History, Theory and Research.

There are 13 chapters plus an introduction in Part III, for a total of 223 pages, sufficient to be considered a book in its own right.

This is going to be another very long post, but in fairness to the chapter authors, who I know have worked hard on their chapters, I need to provide the bare minimum of coverage so that you know what they are writing about.

Because of the length, I will start with an overall review of this section of the book, followed by a chapter-by-chapter synopsis.

Overall review

Overall, the chapters in Part III, on globalization and internationalization and ODDE, are well-written and solid (in more senses than one). Everyone will have their own interests and biases, but the most interesting chapters for me were:

- Chapter 19: by Amir Hedayati-Mehdiabadi and Charlotte N. Gunawardena, on cultural and ethical issues in cross-border distance education; this is essential reading for addressing cultural and ethical issues in any online or distance class;

- Chapter 26: by Jean-Paul Restoule and Kathy Snow, on online course design issues for indigenous learners, which lifts a veil on a massively under-researched topic;

- Chapter 27: by Laura Czerniewicz, University of Cape Town, South Africa, and Lucila Carvalho, whose discussion about equity issues in ODDE were thoughtful and nuanced.

Many of the other chapters though were at a high level of abstraction and would have benefited by being more empirically grounded. This applies particularly to the chapters on international students studying at a distance. This is not only an important potential market for ODDE, but also raises some major cultural and ethical issues. Unfortunately, though, there is little empirical research on international students in ODDE and above all a huge lack of data. Basically, from these chapters, it appears very little is known about such students. Yet many of us have experience of online classes with international students. This experience is not well reflected in this book.

There was also little on the impact of globalized ODDE. In the past, there have been evangelists arguing that ODDE and/or educational technology, in the form of broadcasting, satellites or MOOCs, will be the solution for education in developing countries. We have learned that is not so, but nevertheless there is now a lot of ODDE in developing countries. This section could have benefited from chapters reporting on what has or hasn’t worked with ODDE in developing countries, and why.

There was also very little on ODDE in k-12 internationally in this Part.

Once again, apart from the fact that the topics were globalization and internationalization, there was little coherence between the chapters. The reader will find it difficult to pick out any overarching themes or direction from these chapters. (If you can, please use the comment box at the end of this post). Now for the chapter-by-chapter synopsis.

Introduction to Part III

The sub-editor for this part, Svenja Bedenlier, of Friedrich-Alexander-Universität, Germany, has written the introduction. She writes:

Globalization is delineated to encompass aspects that refer to the global external environment and drivers, the development of the global distance education market, teaching and learning in mediated global environments and its implications for professional development….

The perspective on ODDE aims to provide an overarching view by following the idea of cultural clusters across the globe, comparisons of ODDE systems in an international perspective, and the focus on groups of countries.

A central topic permeating developments within ODDE has been that of culture, and specifically the role of hegemony of pedagogical values and theories in educational technology.

Zawacki-Richter (2009) identified “Globalization of education and cross-cultural aspects” to be a neglected research area at the macro-level of distance education systems and theories.

Bedenliner concludes: The chapters in this section illustrate the array of topics that can be considered mosaic pieces under the heading of global perspectives and internationalization in ODDE. In sum, they provide a picture of a field that is still in the process of becoming – leaving ample space for further engagement in theory, practice, and research.

Chapter by Chapter review

16. Assessing the digital transformation of education systems: an international comparison, pp. 250-266

This chapter, by Adnam Qayyum, of Athabasca University, Canada, argues that:

the digital transformation of education has been underway for decades at differing paces across the world. In this chapter, an education digitization index is proposed in order to assess the extent of digital transformation in various countries.

The education digitization index is composed for four variables:

- digital assets,

- digital use,

- digital labor,

- digital outcomes.

While a lot of research and practice in education has been on digital use – applying particular digital educational technologies – countries with substantial digital assets and a commitment to digital labor are able to transform education systems more readily. Digital assets and digital labor have become more important during the pandemic.

Common examples of digital transformation include institutions offering courses partly or fully online, digital open educational resources (OER), students or teachers using digital platforms to collaborate, and curriculum designed to foster digital skills and competencies as learning goals.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the extent of digitalization of education across the world, as measured by the four variables, although not at the level of detail of a comprehensive international index comparing specific countries across each of the four variables. It is a pity Qayyum does not refer to the work on eLearning readiness or maturity models (e.g. Marshall, 2008) for institutions, which surely would also have some relevance at a national level as well. Nevertheless this chapter is a wide-ranging analysis of key variables influencing digital transformation across the world.

17. The Impact of International Organizations on the Field of Open, Distance, and Digital Education, pp. 267-282

This chapter, by Dominic Orr, of Nova Gorica University and GIZ, Slovenia, looks at the link between international organizations (IOs such as UNESCO and the World Bank) and developments in the field of open, distance, and digital education.

Orr argues that IOs fulfill their mandate, when they bring together multiple actors for collaborative discussion and exchange, and foster solutions on how to collectively solve some of the world’s greatest problems….There has been a long tradition of IOs both promoting digital learning as solution, but also in setting up coalitions for implementing international collaborative operations around these ideas….Harnessing ODDE could be described as a “light-footed solution” and discussing and ideating around ODDE can be achieved without directly coming into conflict with the political and regulatory framework conditions of a specific country or region that formal educational systems and their institutions are usually entrenched in.

Orr provides a convincing explanation of the rationale for the engagement of IOs in digital learning. He then goes on to look at the impact of IOs in practice. He argues that they use primarily three methods:

- ideation, linked to policy change

- digital infrastructure projects

- multi-stakeholder networks

and provides excellent examples of each in terms of digital learning.

Lastly, Orr calls for more and better research on ODDE implementation and adaptation in international contexts, to provide a base for ensuring the work of IOs has greater impact. This article is essential reading for anyone interested the role and impact of IOs on ODDE – and vice versa.

18. Online Infrastructures for Open Educational Resources, pp.283-302

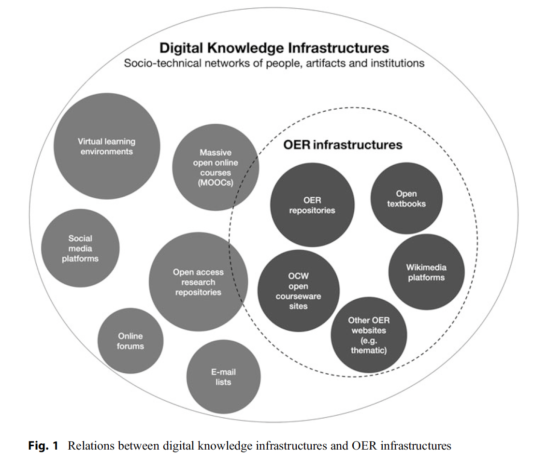

This chapter, by Victoria I. Marín, University of Lleida, Spain and Daniel Villar-Onrubia, University of Coventry, U.K., focuses on digital knowledge infrastructures devoted to the creation, storage, management, and sharing of OER across diverse educational levels and geographies.

Knowledge infrastructures are defined as: ecologies or complex adaptive systems that consist of numerous systems, each with unique origins and goals, which are made to interoperate by means of standards, socket layers, social practices, norms, and individual behaviors that smooth out the connections among them. OER and MOOCs are examples of such knowledge infrastructures

This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of the main OER infrastructures worldwide, and key challenges. The article concludes that there is still room for improvement through research in terms of sustainability, interoperability, users’ awareness, quality assurance, licensing issues, and their socio-technical, pedagogical, and cultural aspects.

Although comprehensive, this chapter is mainly a list and history of OER initiatives worldwide. For those not familiar with OERs in ODDE, this might be useful, but there was not enough analysis of the social and cultural issues in international use and adaptation of OER.

19. Culture, Ethics of Care, Community, and Language in Online Learning Environments: Supporting Adult Educators in a Digital Era, pp.303-320

This chapter, by Amir Hedayati-Mehdiabadi and Charlotte N. Gunawardena, of the University of New Mexico, USA, uses a cultural and ethical lens to examine issues related to community and language to contribute to the design of equitable and inclusive online learning environments, with a focus on adults as learners.

The chapter covers the following topics:

- The concepts of culture and ethics in online learning

- Community

- The ethics of care

- Language

- 10 recommendations for inclusive online course design

- Future research

Here are some ‘nuggets from the article:

- Cultures that emerge online transcend national culture

- What does it mean to be culturally inclusive in online design? Participants must feel a sense of belonging to a learning community, which values different beliefs, worldviews, and educational experiences (which is why I prefer cohort to independent online learning.)

- ethics of care [is] a framework to look at ways online educators can create inclusive spaces for learners to prosper

- Building a culturally inclusive community is a gradual process that takes a collective effort from designers, facilitators, mentors, community experts, and participants

- social presence is a key ingredient of the social environment of online learning, a strong predictor of learner satisfaction in online environments, and a predictor of perceived learning in online courses

- teacher-centered online learning environments with little opportunity for interaction are not conducive to promoting ethics of care.

- Online educators have the ethical obligation to ensure learners are treated equitably.

This chapter so strongly reflects my own philosophy of online teaching that it is difficult for me to be objective, but if there is one chapter in the whole of this book that instructors moving to online teaching for the first time, or instructors struggling to engage online learners, should read, it is this one.

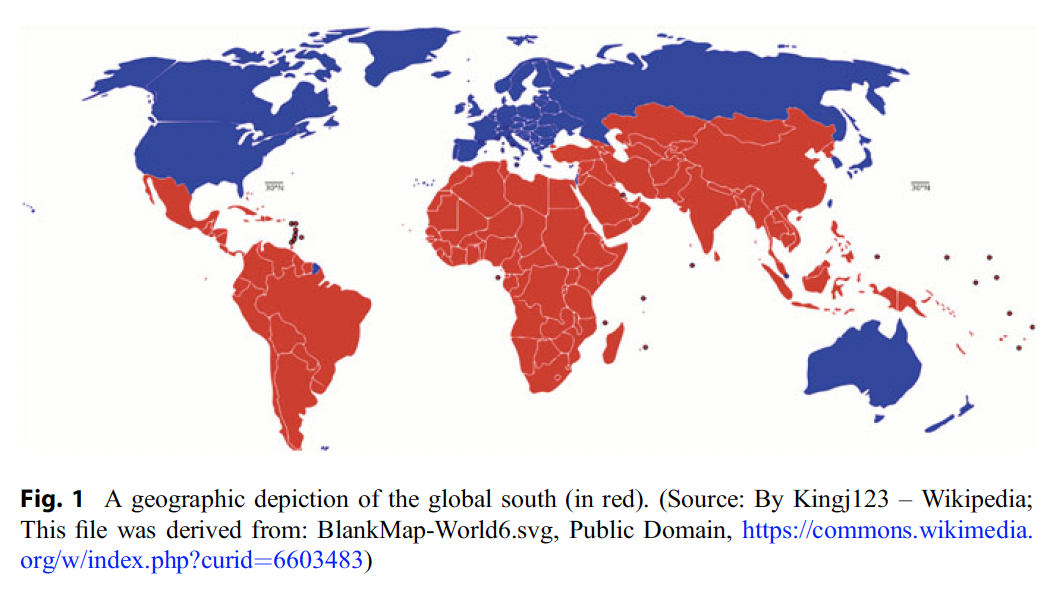

20. Challenges and Opportunities for Open, Distance, and Digital Education in the Global South, pp. 321-336

This chapter, by Tony Mays, of the Commonwealth of Learning, Vancouver, Canada, explores some of the challenges and opportunities for expansion of open, distance, and digital education in the global south.

Mays notes that some of the challenges for expanded ODDE provision [in the global south] include:

- the limited investment in digitization,

- lack of appropriate policy frameworks,

- inadequate funding,

- limited skilled personnel,

- commercialization at the expense of public provision,

- the high cost of hardware and the Internet

- limited technical support

- lack of a common language to scale up ODDE activities.

Mays provides examples of ODDE activities and challenges in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Latin America, and the (south) Pacific Region.

From a review of the literature on ODDE in the Global South, Mays focuses on the following:

- diversity of ODDE models

- policy support

- language

- quality assurance

- continuous professional development

- finance and sustainability

The chapter ends with a discussion of future research directions and the implications for ODDE practice within the Global South.

This is one of the few chapters in the whole book that focuses on ODDE and school systems. However, the vast geographical scope of this chapter makes it difficult to achieve any systematic, deep analysis of the issues facing ODDE in the Global South, of which there are many.

21. Open, Distance, and Digital Non-formal Education in Developing Countries, pp. 337-355

This chapter by Sanjaya Mishra, of the Commonwealth of Learning, Vancouver, Canada, and Pradeep K. Misra, of the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi, India, presents

- an overview of the use of ODDE for supporting non-formal education initiatives (NFE) in the developing world, and identifies issues and challenges

- theoretical insights and findings regarding the use of ODDE for offering NFE

- strategies for making the best …use of ODDE to make NFE accessible to all ….in developing countries.

This is one of several chapters in this section that links ODDE to helping achieve the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. The authors argue that providing need-based quality education to all citizens ….is the way to achieve SDGs and improve the status of a developed country, but, the authors argue, this is not possible through the use of formal education practices alone….Fortunately, many countries have started using ODDE to make NFE more accessible and approachable to the masses.

The authors provide several interesting examples of the provision of NFE through ODDE in developing countries, using low cost technologies such as radio or low-cost mobile phones.

In discussing issues and challenges, the authors note that the poor and least educated in the developing economies are unable to take benefit of NFE due to many barriers including

- situational barriers (those arising from one’s situation in life),

- institutional barriers (practices and procedures that hinder participation), and

- dispositional barriers (attitudes and dispositions toward learning).

After listing many barriers to NFE in developing countries, the authors conclude: to promote the use of ODDE for NFE, developing countries need specific strategies to implement ODDE in NFE contexts. The authors then outline nine such strategies.

This will be a useful chapter for national governments in developing countries wishing to implement the SDGs. Non-formal education is an undervalued tool, and ODDE could be one cost-effective means of providing non-formal education in developing countries.

However, I have problems with the core assumptions underlying the UN’s SDGs. Education and economic development are of course closely intertwined. Without education, economic development is difficult, but economic development is needed to pay for universal access to education. However, neither non-formal education nor ODDE are silver bullets for solving this enigma. There are other factors in play in many developing countries, such as corruption, poor governance, and tribalism. Yes, ODDE in non-formal education should be supported in developing countries, but it is just a small piece in the mosaic.

22.The Borderless Market for Open, Distance,and Digital Education, pp. 356-369

This chapter, by Jill Borgos, State University of New York, Kevin Kinser, and Lindsey Kline, of Pennsylvania State University, USA, highlights the historical, current, and emerging trends on the borderless market for ODDE.

The authors spend some time expounding on the financial expansion of the ODDE market globally. For example: The estimated overall growth in the ODDE industry is projected to reach US$350 billion by 2025.

They also point out that Although ODDE has the technological potential to expand educational access, market forces and profit-seeking service providers may ultimately reinforce existing access inequalities, thus prioritizing the expansion of established global consumer markets, rather than creating new ones.

One of the drivers of the expansion of ODDE is the changing economy: National strategies targeted at reducing unemployment rates and domestic labor shortages, adjusting for the disappearance of low-skilled jobs, preparing an influx of immigrants to transition to the workforce, and meeting the growing demand for skilled labor in healthcare and the tech industries have sought to include the use of ODDE to address existing gaps in the current education level and/or skills of its citizens

They also point out that The sheer magnitude of the financial opportunity inherent in the ODDE market has prompted venture capitalists to increasingly support entrepreneurial endeavors in the education sector; in other words, the increased privatization of ODDE.

They argue that as well as increasing inequality, the increased commercialization of ODDE requires more attention to be paid to quality assurance and ‘consumer protection’.

While these trends are certainly global, the chapter reflects particularly the state of higher education in the USA, where commercial forces, low levels of state investment, and hence high tuition fees, play a much larger role in higher education than elsewhere. Nevertheless it is a useful warning of where we could be going in the next few years.

23. Virtual Internationalization as a Concept for Campus-Based and Online and Distance Higher Education, pp. 371-388

This chapter, by Elisa Bruhn-Zass, of GIZ, Germany, describes The concept of Virtual Internationalization (VI), developed to systematize the impact of digitalization and information and communications technology (ICT) on higher education internationalization.

This is a highly conceptual chapter that attempts to describe and systematise the various ways in which ICTs can facilitate the internationalization of teaching and learning. The chapter provides various rationales and requirements for using ODDE and ICTs for internationalization.

Personally, I am all in favour of making online courses open to international as well as domestic students – which is just one of the many ways Bruhn-Zass suggests internationalization can operate. However the chapter is almost totally lacking in pragmatic examples and ignores the resistance many campus-based institutions have to using online learning in particular for internationalization, fearing that it will compete with the lucrative revenues from on-campus international students. The chapter also ignores the cultural and ethical issues that arise when enrolling international students into domestic online courses.

However, this is not the purpose of this paper, which is to provide a conceptual framework for understanding the virtual internationalization of teaching and learning. You will need to read it to see whether you find the analysis convincing or useful.

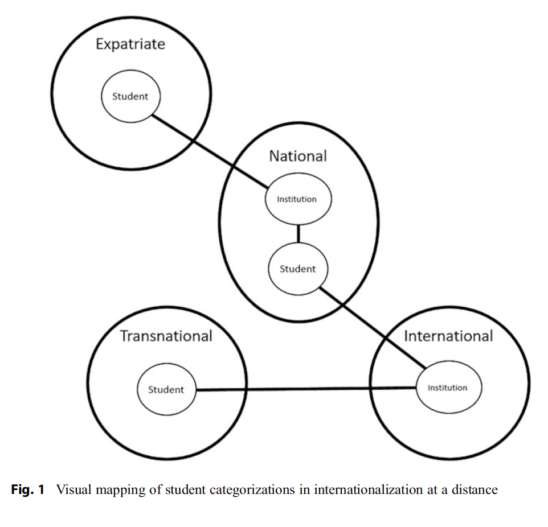

24. International students in ODDE, pp 389-406

This chapter, by Jenna Mittelmeier of the University of Manchester, U.K., outlines complexities in categorizing international students in open, distance, and digital higher education and the ways that their experiences may be distinct from international students who are geographically mobile….and reflects on gaps in current research and suggestions for researchers who include international students in their work.

The author argues that: Internationalization at a distance is distinct from internationalization abroad (which assumes geographic mobility) and internationalization at home (which assumes affiliation with an institution “at home”)….This also means that many sources of international data about international students fail to capture or record the number of international distance students studying via ODDE.

Mittelmeier also argues for more attention to be paid to overcoming barriers for international ODDE students: It is recognized that transitions do still exist in ODDE and that international distance students still encounter new educational norms and values while undertaking a degree abroad.

Lastly (as do most authors in this book) she calls for more research: Knowledge about the experiences and contributions of international distance students has remained relatively under-researched and under-theorized in comparison with other aspects of ODD.

As in the previous chapter, there is a lot on definitions of international students and the difference between ODDE and face-to-face international students. What is more striking though is the lack of data on international students in ODDE. Without data, it is not clear whether this is a big or a small problem. I suspect that the issues facing students who are living in another country are much greater than for those studying a program at home from another country, but without data, we don’t really know. There is not much practical guidance in either chapters though for instructors on how best to support international students in online courses. This is a great area for more systematic research.

25. International Partnerships and Curriculum Design, pp. 407-424

This chapter, by Tanja Reiffenrath and Angelika Thielsch, of the Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany, surveys linkages between international partnerships and curriculum design…this chapter introduces different curriculum design models and their implications for international partnerships.

The authors propose three ‘models’ of curriculum design and looks at their pros and cons:

- process models: In process models, orientation for the development of a (new) curriculum derives from the attributes and features which an institution marks as relevant for itself…Here, not only assumptions about teaching and learning must be somehow aligned, but also the strategic orientations of the institutions involved

- product models: In product models, the focus is on developing and communicating transparent outcomes…but care should be taken not to be overly prescriptive when writing learning outcomes, especially so when a program addresses an international target group and aims at intercultural competence development in an online setting

- post-modern models: These seek to apply a less fixed and more relationship-based approach to designing curriculum and demand that power needs to lie in the hands of teachers and learners.

The chapter is very much influenced by the European context. Currently more than 280 higher education institutions are part of so-called European Universities (EUNs), i.e., European HEI alliances that are piloted in two rounds of an Erasmus+ call. These aim at transforming the European Higher Education Area, a goal that will involve not only substantial efforts in linking campus (infra)structures but also a collective push to make curricula more flexible in order to allow for the “seamless mobility” – physical, virtual, and blended exchange opportunities – envisioned in the call.

I have to say I was really disappointed by this chapter. I was expecting to learn how joint curricula were actually developed in different international partnerships, but again this article was a highly conceptual piece that did not seem embedded in the actual practices of joint international online programs.

26 Conversations on Indigenous Centric ODDE Design, pp. 425-440

In this chapter, by Jean-Paul Restoule, of the University of Victoria, Canada, and Kathy Snow, of the University of Prince Edward Island, Canada, the authors dialogue their experiences working with Indigenous people and designs in open, distance, and online teaching and education….By sharing highly contextualized narratives from Canada, [the authors] aim to increase the global dialogue around decolonizing ODDE.

The authors point out that Very little has been written about the conflict between Indigenous worldviews and the biases inherent in educational technology. They begin with a description of indigenous epistemology (e.g., experiential, personal and highly contextual). The authors conclude that, at least in Canada, strategic change to support Indigenous centric digital learning has not yet been addressed.

They then report on their own research in this area, using ‘kitchen table talks’ (a form of storytelling). Both authors discuss their own experiences in online learning with indigenous students, one teaching a MOOC and the other teaching a biology course in a nursing program. These are highly personalized descriptions but provide some very interesting insights into the needs of indigenous online learners.

They conclude: While relationship-building in learning is not exclusively an Indigenous domain, literature indicates it is a must for Indigenous students. The authors talk about ways that Indigenous students use technology to connect and create safe spaces for themselves beyond the course, with social media platforms.

This was one of the most interesting chapters I have read so far. Many of the challenges faced by Indigenous online learners, such as the lack of personalization and ‘belonging’, are common for many online learners but it seems they matter even more for indigenous learners. Both authors were reporting on courses with a heavy emphasis on content presentation, and again such courses present learning challenges that are not unique for indigenous learners. I felt the authors were overly critical of LMSs, which can be used for community-building, but that requires changes in the overall course design.

Nevertheless, this is a topic that needs much more research. Indigenous ways of learning need not only to be recognised and supported in online learning, but can also be valuable for many non-indigenous online learners too. This chapter is a good start for thinking about these issues.

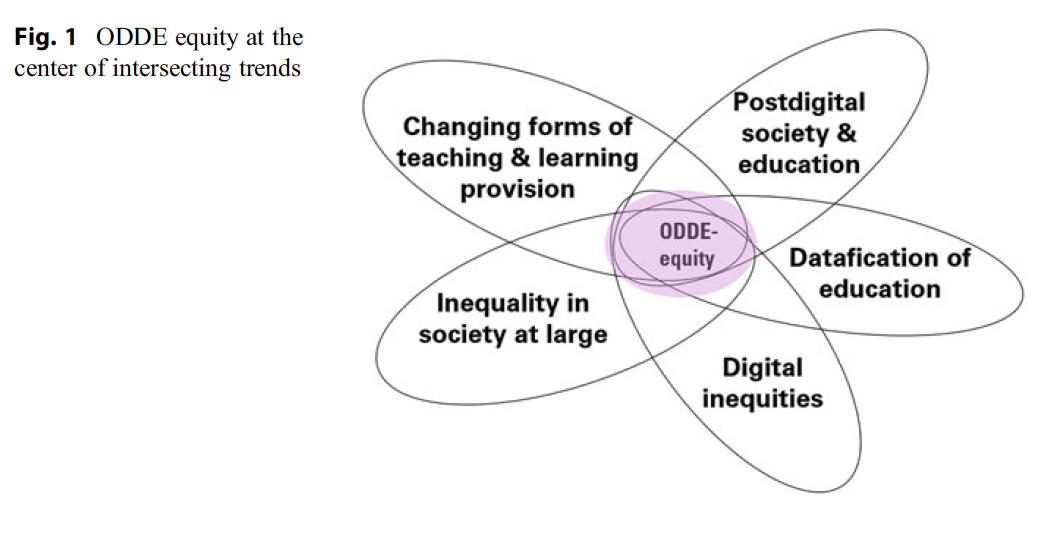

27. Open, Distance, and Digital Education (ODDE): An Equity View, pp. 441-459

This chapter by Laura Czerniewicz, University of Cape Town, South Africa, and Lucila Carvalho, Massey University, New Zealand, addresses the following questions: [in ODDE] which interests are served, who is advantaged, who is disadvantaged? How can educators best support students’ equitable participation in networks? How can educators encourage all students to connect to others and to learning resources?

The authors note that digitalization increases inequalities between rich and poor countries: Questions about digital data pertain to how it is used, owned, shared, understood and made invisible. The pandemic saw a massive growth in private companies becoming stakeholders in education; for many their business models are forms of platform or surveillance capitalism. It is thus likely to be more disadvantaged institutions which have no choice but to use so-called free systems which exploit their data.

The authors also draw attention to how digitalization is leading to changing forms of teaching and learning provision, such as unbundling…..such unbundled forms of provision have the potential to exacerbate class divisions as they focus on vocational and practical forms of education, leaving elites to benefit from classic (and with higher status) liberal arts education.

They also point out how the move to emergency remote learning during the pandemic highlighted the digital divide, further increasing inequities.

The authors draw on these developments to explore theories which can help researchers and practitioners understand and analyze these inequities. They draw particularly on the work of Bourdieu and Sen and Nussbaum. The authors conclude: In the context of ODDE, people need digital capabilities that go beyond access to technologies, towards being able to confidently communicate, problem-solve, maintain themselves safely online, so that they can fluently navigate our postdigital world.

The authors end by arguing that Researchers, educators, learners and policymakers need to come to grips with how the infiltration of technology, edtech services and new business models are leading to differentiated and inequitable systems and how institutions are reshaping the nature of what it means to be a “have-not” and a “have” in postdigital open and distance digital education.

This is a very thoughtful article on equity and ODDE, avoiding some of the simplistic analyses that promote or criticise ODDE for reducing or increasing inequities in education.

End note

This has been another very hard slog. (If you are still reading this post, please use the comment box at the end to let me know! I hate to think no-one is reading these reviews).

I am now approximately one third of the way through the book. I hope I will live long enough to finish it. There is a lot of good stuff in Part III, but, my heavens, it was hard work to unearth it.

I hope I find Part IV, on Organization, Leadership and Change, more interesting and accessible – I do after all have my own chapter in this Part. Alors, en avance, mes amis!

References

Marshall, S. (2013) Using the e-learning Maturity Model to Identify Good Practice in E-Learning 30th ASCILITE Conference, Macquarie University, Sydney

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Thank you for your hard work Tony – much appreciated! I shall look forward to your review of Maxim’s chapter on marketing. These days I find myself writing about money (and the lack of it) in online learning more than any other topic.

What a terrific constellation – Tony Bates about Zawacki-Richter’s (et. al) book! I trust coming out of the book is just very good timing and Tony’s comments are extremely helpful to digest this valuable holistic attempt.