Many instructors struggle with assessment of any kind, but particularly with online assessment if they have never taught online before. What they try to do is to apply on-campus assessment practices to an online environment, which is like trying to make a fish walk.

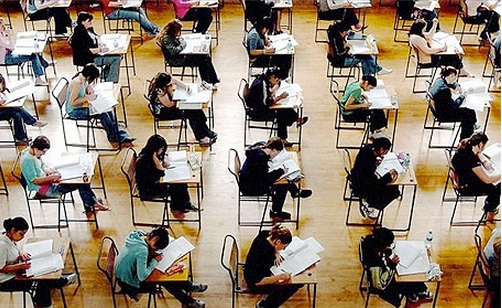

This was a particular problem during Covid and emergency remote teaching. Online proctoring equipment and software were used in an attempt to replicate in-classroom exam supervision. It became ridiculously intrusive of a student’s privacy and was often not successful in preventing students from ‘cheating’. However, the question also needs to be asked: even if online proctoring works as intended (i.e. no cheating), would the assessment method still be appropriate? I’ll discuss that further below.

Now, following emergency remote learning, some instructors are continuing to teach online, but are at the same time requiring online students to come to campus for an invigilated or proctored, in-person exam, sometimes as much as three times a semester. Obviously they do not trust online assessment.

More importantly, where this is happening, institutions are asking how such courses should be described to students: are they fully online or are they hybrid or blended courses? There is an interesting discussion on this topic currently in the WCET forum, WCET Discuss (open though only to WCET members). Again, though, this does not deal with the issue as to whether requiring otherwise online or distance students to come to a campus for their assessment is a wise policy. I believe that it is not.

What are we assessing?

Put simply, assessment is an evaluation of how well a student meets the learning objectives of a course or program of study. So it comes down to: what are the learning objectives for the course, and, more importantly, what is the best way to assess students on the objectives?

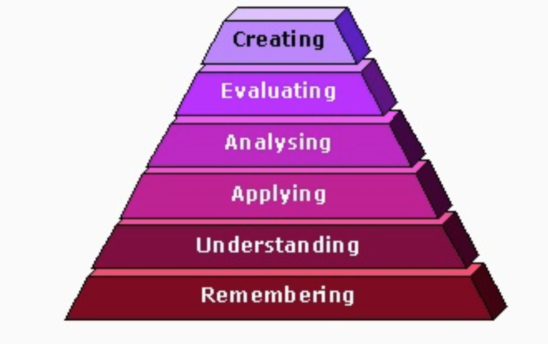

We could get into a discussion of Bloom’s hierarchy of objectives, but let’s make a gross oversimplification between memorisation and comprehension on the one hand, and analysis, application, critical thinking, and problem-solving on the other. Another useful but also somewhat hazardous distinction is between motor and thinking skills. I am going to suggest we need different ways to assess these different types of learning objectives; one size does not fit all.

Organisational issues

Also, for the sake of argument, let’s also assume that any form of assessment should take into account functional or organisational factors, such as when and where the assessment can take place. For instance, should it take place just at the end of a course, how best to avoid or discourage cheating, who should do the assessment, and how much time or resources are available for assessment?

We should also accept that after over 100 years of assessment in education since the start of the industrial revolution, we have settled into well-worn and comfortable assumptions about how assessment should be done. However, we are no longer in an industrial age, and so these assumptions should be open to examination (no pun intended).

Memory and comprehension

Memory and comprehension are very common learning objectives in all subject areas (another important variable regarding assessment – what is appropriate assessment for history is not necessarily appropriate for physics).

The tendency in the past has been to assess memory and comprehension through objective testing (right or wrong answers). You either know a fact or understand a concept, or you don’t. The Great Game was the conflict between Russia and Great Britain between about 1830 and the end of the 19th century over control of central Asia (memory). The reason for this conflict was Great Britain’s fear that if Russia controlled Afghanistan, it could easily move into India and thus threaten Britain’s most important colony (comprehension).

Understanding this principle can help explain or understand Russia’s motive for the invasion of Ukraine or the Taliban’s power in Afghanistan (analysis, application). Thus memorisation and in particular comprehension are often building blocks to the higher level learning objectives of analysis, application, critical thinking and problem-solving.

One of the concerns about online assessment is that instead of memorising important facts and concepts, students will just look them up on Google or some other search engine. With regard to comprehension, analysis and the other higher level objectives, the concern is that students will use online tutors or other external sources to provide the answers, without doing the learning or thinking themselves – hence the need for online proctoring.

Memorisation is still important in particular contexts. You don’t want a surgeon having to look up the name of a muscle in the middle of an operation, or a bus driver to use Google Maps on a bus route (although both have been done). But I will argue that for many purposes, in today’s digital society, immediate memory is not necessary for many purposes. Much more important is to know how to search for information, how to evaluate its validity, and then how to apply it. There is now just too much information and knowledge available for anyone to remember it all.

At school, my English teacher made us learn by heart over 1,000 lines of Hamlet so we could choose the right quotation to support our answers for the exam. (“Was Hamlet mad? – No, only those who had to study him.”). It got me a reasonable mark in the exam but it killed any love I had for Shakespeare. It was only years later, when I saw a live performance of ‘Richard the Third’ at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-on-Avon in England, that I began to appreciate Shakespeare. My point is: is having to learn by heart 1,000 lines of Hamlet the best way to teach appreciation of Shakespeare? My answer is a resounding ‘No!’ Assessment should strive for a higher objective. Memorisation should be embedded in context.

So: why are you still testing for memorisation or comprehension? Is it absolutely essential, or would it be better to focus on other objectives? If you are concerned with students acquiring the higher learning objectives, direct supervision is unlikely to be necessary, as each student will need to find their own route to analysis, application, critical thinking or problem-solving. Online learning can track that individual journey for each student.

The assessment environment

When students are in school or college during the day five days a week, it is obviously convenient for everyone for assessments to take place within the institution during regular hours. Students can then be invigilated by instructors who would be there in any case.

Requiring students who have signed on for a fully online, that is, a distance course, to come in to do their assessment on-campus may be convenient for the instructors, but it is certainly not convenient or even possible for the students. They have deliberately signed on to an online course because they can’t conveniently attend the campus. They may have work commitments or young children to look after or may be too far distant from the campus to travel, without greatly added expense (such as overnight accommodation).

If you are teaching an online course, you need to use appropriate online assessment. This does not mean replicating an in-person, vigilated, time-limited exam, but finding ways to assess the learning objectives that can be done effectively online. In other words, assessment must not only measure what students have learned, but must do so in a way that meets the requirements of students as well. This means doing things differently from on campus. Again, different does not necessarily mean worse. Indeed, online assessment can be more authentic and examine more deeply than traditional paper and pencil exams.

Designing online assessments

Here are a few basic examples that exploit the unique affordances of online learning (for more, see Conrad and Openo, 2018). Each of these should directly link to the course’s main learning objectives.

1. Continuous assessment

This requires essentially the use by students and instructor of a learning management system, such as D2L, Blackboard Learn, Canvas, or Moodle. These provide an online work environment shared by both students and instructor. Basically, an LMS can track most of the work that students do on an ongoing basis. They can post their work, either in draft or final form, they can participate in online discussion forums, and they can take tests or small assessments ranging from multiple-choice questions to short paragraphs to full essays. (If necessary, you can link to recordings of live video lectures, or streamed video lectures can be embedded within the LMS).

The work given to students should enable them to draw on their own experience and learning. Because the range of online activity is so wide and in relatively small chunks, it makes cheating more difficult or requires more effort to avoid than actually doing the work. This is particularly true if students are given individual or small group projects to do. Many online students are older and more mature and can often draw on their unique personal experience in responding to questions. (Make sure though that you don’t overload students with activities: most students can spare no more than eight hours a week on all activities associated with a three credit course).

Using a matrix with the name of students on one axis and a list of student activities throughout the course on another axis, the instructor can track easily what each student has done (a tick) or grade each activity. Some instructors post the other students’ scores on each activity anonymously, so a student can see how he or she is doing in comparison to the group. You could also allow a student to re-do an activity if they are not satisfied with their previous grade. This use of the LMS also allows for continuous feedback and monitoring of students as well as assessment.

If the activities are linked to clear learning objectives, it should be possible to track the student’s development and level as the course progresses. This may be sufficient in itself to give a grade at the end of the course, although some instructors also prefer to give students a chance to upgrade with an exam at the end of a course. It is usually easy to spot cheating on the end of course assessment if there has been continuous assessment throughout.

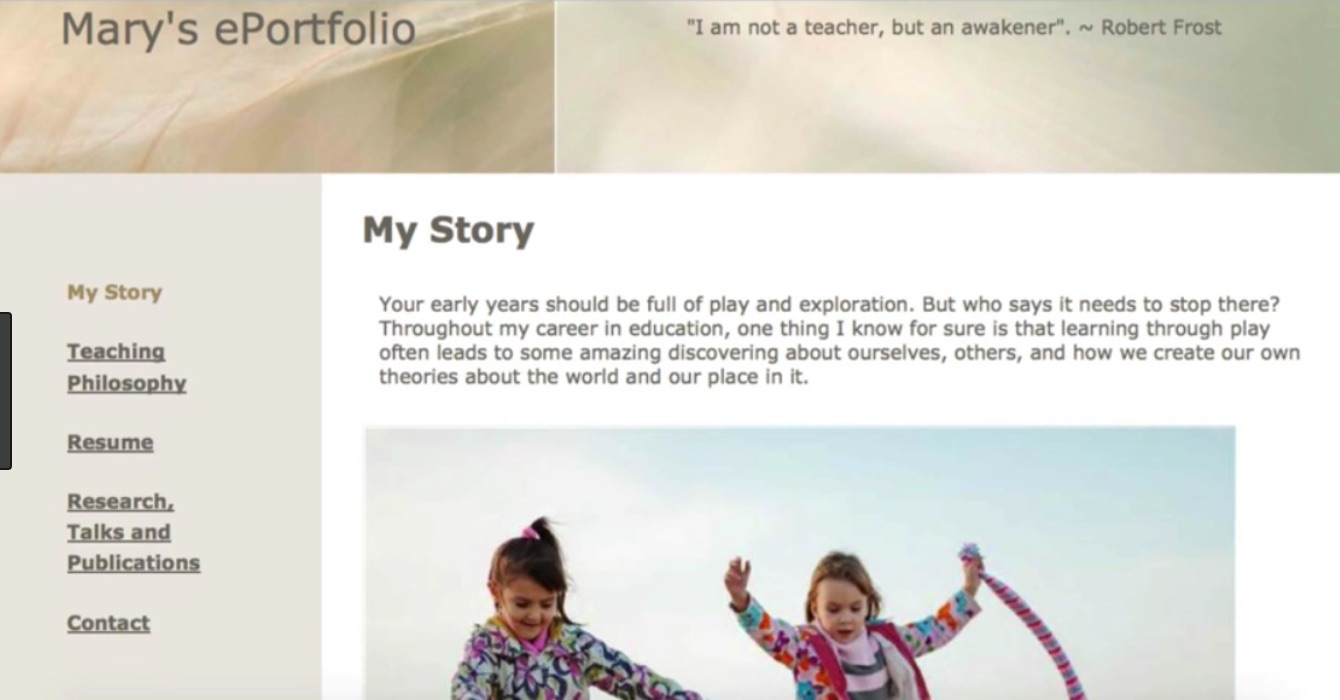

2. e-Portfolios

Many learning management systems now come with an embedded system that allows students to create their own online portfolio of work. If your LMS does not include an e-portfolio, they can download specific e-portfolio software. (Choose one for the whole class to keep the instruction simple). Students can then do a number of things:

- use the e-portfolio as a personal blog to reflect on their learning

- use it for organising any notes or observations they may have made

- use it for project work such as collecting data; this might include video or recordings they have made, or showing any home experiment they may have done

- use it in response to activities that you ask them to do, such as short answers, with your feedback and even their response to your feedback.

The aim is to build a portfolio of work that demonstrates what the student has learned. Again, this can be assessed on a continuous basis (preferably) or as an end of course final assessment.

3. Use your imagination!

There are many other possible ways to assess students online without using proctoring software. The method of assessment will vary from subject to subject, so it is difficult to give general rules, but the important thing for the instructor before the course begins is to:

- imagine the context of the online learner,

- identify the main learning objectives to be covered in the course in terms of both content and skills

- determine appropriate methods of online assessment,

- ensure that students (and you) are not overloaded with work

then build the course around these four main requirements.

What won’t work is merely repeating your in-class lectures then trying to assess the student learning the same way you do on campus. You need to design your courses for the environment in which students are working without lowering standards and for most instructors this will require some imagination and adaptation of their assessment methods.

Reference

Conrad, D. and Openo, J. (2018) Assessment Strategies for Online Learning: Athabasca AB: Athabasca University Press

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.