What a co-incidence!

A few months ago, I wrote a series of blog posts on the crisis in higher education, arguing that it had become too expensive. Universities in particular needed to find ways to reduce costs while still maintaining quality. Last month, I reviewed eight free AI tools offered by Contact North for instructors and students in Ontario (although nearly all could really be used anywhere). Immediately afterwards, I was asked to write a feasibility report for the United Nations on a proposal to establish a global online university for STEM education for the poorest in the least developed countries. What happy co-incidences, especially for someone like me who was supposed to be retired. At least they have forced me to continue to use my brain.

I want to use these three quite different experiences to reflect on the implications of AI for teaching and learning. And no, I am not going to say that AI is the answer to all our problems; it has an important role to play but, of course, it’s complicated, which is what makes life more interesting.

Summarising the issues

Before I get into the meat of the argument, some background.

1. The cost of higher education

The argument here is simple: post-secondary education has become too expensive. Governments are either reducing direct funding or not keeping up with inflation, and/or student fees are getting to the point where students (and parents), at least in more economically advanced countries, are beginning to question the return on investment. The problem of cost is particularly acute in developing countries, where demand far exceeds the supply.

Despite all the developments in technology over the last 100 years, we still have more or less the same design for the bulk of university teaching: large lectures, and (if you are lucky) smaller in-person seminars and lab work. Sure, more of this may now be online, but in general, the standard, traditional university teaching pedagogy hasn’t changed much. For more on this see my earlier blogs.

2. The march of AI

In the last few years, AI has really taken off. In particular, the use of large language models has resulted in a wide range of (possible) educational applications. AI is excellent at finding and summarising information and giving automated feedback to and interaction with learners. It can also be very useful for planning curricula, enabling students to make career choices, and selecting courses and programs and institutions. However, at the moment, it is mainly being bolted on to traditional teaching and learning (see my posts on this). It is not being used so far to radically re-think how education could/should be provided.

3. STEM education in the world’s poorest countries

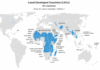

The United Nations defines least developed countries (LDCs) as low-income countries confronting severe structural impediments to sustainable development. Approximately 14% of the world’s population lives in LDCs, which are highly vulnerable to economic and environmental shocks and have low levels of human assets. There are currently 44 countries on the list of LDCs which is reviewed every three years. LDCs are countries with gross national income (GNI) per capita of less than US$1,025 per annum. (In comparison, the GNI of Canada in 2023 was US$62,400.) Nearly a third of the population in LDCs live in extreme poverty (living on less than $2.15 per person per day).

However, the working-age population in LDCs is expected to double by 2050, rising from 610 million to 1.2 billion. That’s a lot of people to educate (currently 60% of the global youth population), but at the moment the participation rate in higher education in LDC’s is only 11%, compared to the global average of 40%. Participation in STEM subjects is even lower. It is clear there is not a snowball’s chance in hell over the next 25 years of finding places for half a million new students a year in each of the LDCs, using the current model of higher education; hence the UN’s interest in a possible global online university for the LDCs.

Disclaimer

I am not going in the post even to attempt a full evaluation of the benefits, limitations and issues with the use of AI for teaching and learning in higher education. I don’t have the expertise or experience to do that. Instead, I want to focus on just three issues that have, from direct experience, jumped out at me. These may be obvious to many (at least when they think about it) but nevertheless these are existential issues for higher education.

1. Undergraduate university teaching must radically change

Having reviewed Contact North’s AI tools, it is clear to me that university teaching will need to move away from information transmission, and especially the delivery of information through lecturing. Existing AI tools enable the design of undergraduate curriculum, the delivery of content, and the assessment of comprehension and understanding. Lecturers are no longer needed – but teachers are. Students have discovered this already. There is strong evidence that students are using these tools. No need to get on the bus to campus or drive across town for lectures – they can get this on their computers.

However, this leaves a lot of teaching activities that will still need an expert in the subject. AI has problems with ‘outliers’ – cases that are unique or unusual, but in fact may be critical for full understanding of a subject. This is why I focus on undergraduate education, which in most cases has a well-defined and relatively unchanging base in most subject areas. Instructors are needed to direct students to what it is important to learn, and to teach in newly emerging discipline areas. They are also needed, at least given the current state of AI, to develop essential learning skills: critical thinking, creativity and innovation.

This is in fact good news for faculty, because these are the most challenging and interesting parts of university teaching, and the ones most needed. However, this will mean moving away from lectures to more creative teaching methods, such as team work, problem-solving, apprenticeship (modelling), and real-world applications. Furthermore, these need to be developed at scale, to enable large numbers of students to participate, which brings me to my next point.

2. AI needs to move away from replicating poor current teaching practices to radically changing teaching practice

What disappointed me most about Contact North’s AI tools is that they were designed primarily to model less effective – if common – higher education teaching practice. The AI tools were excellent at replacing university lectures and giving feedback and assessment on student’s comprehension and understanding, but they did nothing to facilitate critical or creative thinking. I was reminded that AI is following standard practice in technological revolutions of mimicking old, inefficient ways of operation. True productivity gains came only when standard practices were radically changed to exploit better the innovation.

Comprehension and understanding are essential to moving to critical thinking, but I would like to see the next generation of AI tools build on its strength in teaching comprehension and understanding and finding ways to work with human instructors to facilitate higher levels of learning. Also we need our institutions to change their standard teaching practices to exploit better the potential of AI tools,integrated with other technological changes, such as online and blended learning.

3. The world needs massive changes in the higher education system – and AI should be part of the solution

I don’t believe that everyone needs to go to university, but everyone needs an employable skill or expertise, so they can be productive and contribute to solving many of the world’s challenges, such as climate change, wars and poverty. This requires at a minimum good quality education. In particular, the poorest countries in the world have a pressing need for local scientists, educated and ethical politicians, problem-solvers, business entrepreneurs, and innovators.

The focus understandably to date of the United Nations and donor agencies has been on building up primary and secondary education in the least developed countries. The more successful this strategy is, though, the more demand there is for post-secondary education. The numbers are staggering – half a billion young people over the next ten years. (This is a rough estimate – give or take a million either way). How to meet this demand?

Again, current methods of post-secondary education frankly are incapable of meeting such a challenge. We need to use radically different methods to the traditional higher education model. Bangladesh provides a good example. It has an open university with more than one million registered students. The UN is considering an online university for least developed countries – some of which do not yet even have a connection to the global internet. But these are challenges that can be overcome, using modern technologies (satellite internet connection, for instance) and yes, AI. Basic science education in particular lends itself to the kinds of AI tools showcased by Contact North, thus freeing up scarce science faculty to work on graduate education.

In conclusion

It is an understandable human reflex to worry about losing one’s job to technology in general and AI in particular. However this fear assumes that there is a finite demand for labour. In the education field, the demand globally is so great that it could be considered almost infinite.

AI and other related technologies such as online learning offer opportunities to do things differently, to meet better the huge challenges we are facing, to use our faculty’s expertise more productively. However, it is not technology that is the main challenge. Instead it is re-thinking the standard ways we do things, such as the standard teaching model of higher education. Technology is not the issue here – we – the humans – are the issue. We need to change.

Over to you

Where do you stand on these issues? Am I being realistic in thinking that if we change, we can not only save our jobs but improve the world – or am I a fool, dazzled by the latest technology and unaware of the power of commercial interests to disrupt this idealism? Please use the comment box at the end of this post.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

AI can help Higher Education leapfrog, especially in the least developed countries. Examples like the African Virtual University, which I led from 2007 to 2020, and which helped dozens of higher education institutions experiment with open distance and e-learning, may be helpful for the proposed global UN online university.

AI can help do faster, better and cheaper,. My company, Subula subula.com, is helping higher education institutions understand the potential of AI for teaching, learning, research, and administration. How AI can help save time and resources through prediction, automation, sensing and detection. We help train top leadership and develop AI strategies. I am convinced that higher education leaders must be enabled to make informed decisions and guide their institutions to navigate the complexity of AI integration.

Dr Bakary Diallo

Founder Subula e.U

Former Rector of African Virtual University

Around me, academic inflation is quite common, meaning that academic credentials alone are no longer the sole objective of learning. As a high school mathematics teacher, I am particularly passionate about delivering highly engaging math classes. I am currently developing an experimental mathematics curriculum system. I hope artificial intelligence can assist me in designing this curriculum, primarily to ignite students’ interest in learning mathematics, stimulate their critical thinking, and cultivate a mathematical learning habit that combines hands-on exploration with rigorous logical reasoning. However, I’m still exploring how to best leverage artificial intelligence to achieve these goals effectively!